The Cavaliers (17th Century)

Contemporary Events

- The Protestant Reformation had ended. In many areas Protestantism was firmly established and found a way to more or less co-exist with Catholics. France and Spain are the major Roman Catholic powers. Britain, northern Germany, Scandanavia, and Holland are largely Protestant.

- Henry IV of France is assassinated in 1610. King Louis XIII reigns until 1643 under close advisement with Cardinal Richelieu (who passes in 1642). Louis XIV succeeds his father in 1643, at the age of 5 years old and under the advisement of Cardinal Mazarin. Louis XIV reigns until 1715, during these 72 years his court will achieve a standard of grandeur that other monarchs will aspire to match, but none will parallel. This includes the palace outside Paris at Versailles.

- In England, the throne passes to James I (son of Mary Queen of Scots, formerly James VI of Scotland) after the death of Elizabeth I, ushering in the Jacobean Era. During his reign radical Protestants grow in strength. They opposed the Church of England and sought to “purify” ecclesiastic ritual from all things “Roman”. The Puritans are the leaders that will rise up in opposition to the English monarchy and the same group that flee to Holland and eventually sail the Mayflower to the “New World”. They settle in New England.

- James I’s son is Charles I. He assumes the throne and makes many waves among the Puritans and by levying heavy taxes without Parliament consent. Civil war breaks out in 1642, Charles I is beheaded in 1649. Monarchy is abolished and the Commonwealth (a republic) is proclaimed. Oliver Cromwell (a Puritan) is the figure head of this republic until his death in 1659. Civil war looming again, the Monarchy is restored in 1660 placing Charles II (son of the previous Charles) on the throne. He had fled to the court of Louis XIV, bringing a taste for French life with him upon his return to England.

Early Baroque (Cavaliers) – 1625-1660

The Laughing Cavalier is a portrait by the Dutch Golden Age painter Frans Hals in the Wallace Collection in London, 1624

Frans Hals’ The Laughing Cavalier (1624) epitomizes the characteristics of Cavalier male fashion.

–a low crowned, wide brimmed Cavalier style hat

–an unstarched falling ruff

—a soft doublet with vertical slashes in the sleeves.

–he wears a sash high on the wiast that gives the illusion of a shortened torso

— a long curling moustache

–fabrics are quite lavish

–delicate lace cuffs.

Portrait of Henri de Lorraine-Chaligny, Marquis de Mouy et comte de Chaligny. Museum of Fine Arts, Reims. France.

This Cavalier gentleman has a falling band style collar, possibly attached to his shirt. His doublet features paned sleeves, as well as paning in the upper torso. The peplum of his doublet is truly a series of wide pecadils (individual tabs attached at the waistline).

His breeches–tapering to the knee–are softly constructed without padding between the layers. The overall silhouette becomes deflated when compared to the Elizabethan period.

The very fashionable Cavalier below is wearing the wider and longer (just past the knee) Slop breeches and hair style that finds favor during this period. We can clearly see the shape of the cavalier style hat complete with multiple ostrich plumes. He wears boots, which are the most common footwear for male Cavaliers. His boots have a deep cuff just below the knee (this is shown in the previous Henri portrait in red).

A detail from: Gentlemen of 1625-1630, for after Abraham Bosse, vintage engraved illustration. Magasin Pittoresque 1857.

The white “cuff” with the lace edge is either boot hose (stockings that are edged in the linen and lace cuff that are worn folded over the boot cuff) OR a decorative extension at the bottom of the breeches. Both decorative techniques are quite common during this time. It is difficult to discern from this painting which decoartive technique is being employed here.

Daniel Mijtens portrait of Henry Rich I, the first Earl of Holland. 1640

Henry Rich I (below) portrays a stiffer silhouette than the previous men. His hair is also shorter. However, he is not wearing what I would classify as “plain dress”.

If I had to identify his place in the society of his day based on the clues that his clothing was giving me, I would classify him as a conservative royalist. I would not consider him a Puritan.

He is fashionable, yet a bit retrained. He is not going to the extremes of Cavalier dress, but is certainly influenced by it.

This young Cavalier lady below shows many significant features of the styles of her day.

This young Cavalier lady below shows many significant features of the styles of her day.

The hairstyle is a signature 17th Century coiffure. The top layer of the hair is drawn back into a chignon/bun. The rest of the hair is cut relatively short and hangs down in soft curls.

The bodice of her gown features a slightly shortened torso–greatly shortened when compared with the Elizabethan/Jacobean period. Her sleeves are getting shorter, stopping a few inches from her wrist. Forearms become more visible as fashion progresses through the period. Her gown splits in the front, revealing a decorative petticoat called a modeste. Underneath the modeste, there would be at least one more additional petticoat–the secret. The number of petticoats beyond the secret would vary based on personal taste and changes in the weather.

I have recently found evidence of French women wearing drawers beneath their petticoats. However, in England and most of Europe, the wearing of drawers by women was considered indecent. The majority of European women during this time would remain rather “free” beneath their petticoats.

Plate by Callot of a French commoner, 1625

This plain dress lady in the Callot plate to the right wears a bodice and skirt combination as an alternative to a gown. This back view allows us to effectively see the construction of her sleeves–softly pleated into the armscye–and her coif. Her peplum is created with pecadils. Her skirt is gathered or pleated into a waistband.

Plate by Callot, 1630

The plain dress lady in the Callot plate to the left wears a coif variation that resembles a veil from earlier days. Her bodice is short waisted and also features pecadils. Her skirt is looped up revealing her modeste.

Notice how thoroughly covered she is in comparison to the previous Cavalier style lady (two images above). She follows current fashion in the construction of her garments, but in a modest and conservative way. Very little lace is used in plain dress and garments are made of sturdy “plain” fabrics. Wools are greatly favored, though linen and cotton are also often used. Plain dress subscribers could wear clothing employing the full spectrum of available dyes. When thinking of the most famous plain dressers (Puritans and American Pilgrims), a common mistake places them in high contrasting colors such as black and white. The truth is that black dye was extremely expensive, resulting in fabric of this color being quite pricey. It is more accurate to envision this group of people wearing a wide spectrum of “autumnal colors”, such as mustard, crimson, rust, green, brown and even blue.

DRAWINGS BY WENCESLAS HOLLAR, circa 1650 English Women’s Dress of the 17th Century – Wenceslas Hollar Engravings, Plate No 26

The lady in the Hollar drawing to the right wears a double layer collar that covers the low neckline of her gown. This collar is likely not attached to her chemise, but is a separated accessory. She is wearing a capotain on her head. These hats could be worn over a coif. It is difficult to discern if that is happening here.

On brief consideration, I would consider her plain dress as well. However, the lace edging her collar and cuffs suggests some personal fashion indulgences. She is not completely uneffected by the Cavalier fashions. The inscription on this engraving identifies her as a “Merchant’s Wife of London.” It is quite possible that she is not fully a plain dress advocate at all. She may be merely following the fashions her pocketbook allowed based an a more “middle class” status. Eventually, the captain hat will become unique to Puritan dress.

Portrait of Princess Magdelena Sybilla, 1635.

This Cavalier lady wears the very popular virago sleeve. This is a paned sleeve that is drawn into the arm creating small puffs.

Notice how she has adapted her exaggeratedly long waisted bodice to the prevailing fashion of a shortened torso by the addition of a sash coordinating with her sleeve decoration. This fashion anomaly is evidence that not everyone discarded favorite clothing pieces as fashions faded, but rather adapted them in the spirit of the new fashions.

Her hair is a fine example of the signature 17th century coiffure.

A bit of trivia for you, dogs in paintings often have symbolic significance–linking the subject to a particular aristocratic family. It is quite possible that this is her beloved pet OR a clue identifying her as the mistress of a powerful noble man–possibly even one of the kings.

(Since the title of this particular painting is: Princess Magdalena Sybili, however, this is probably a beloved pet. Specific breeds of dog and types of animals are associated with specific noble families, nonetheless.)

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Valazquez, Young Lady, 1635

This Spanish woman wears a mantilla (a lace veil with the express purpose of covering the hair, and thus honoring God. Today, this practice that is still common in the Catholic church, especially among the elder generation).

Use of the mantilla begins in the 17th Century. At this time it is a distinctly Spanish style.

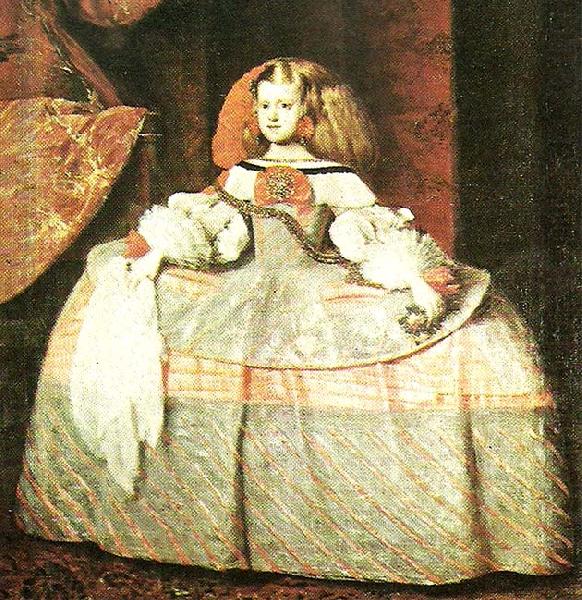

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Valazquez, The Infanta Don Margarita de Austris, c. 1660

This princess below wears fashions that are uniquely Spanish during this era. The wheel drum farthingale survives in a style of Spanish court attire given the name guardinfante. It takes on an oval silhouette, rather than a round one, however.

The wide stiffened peplum of her bodice is referred to as a basque. This extremely wide silhouette is both old fashioned–clinging on to past fashions as well as eerily forboding of styles to come in the mid 18th Century. She would most likely be wearing tall chopines underneath this get up, in an effort to balance the width of this silhouette with some added height. Chopines were mule like slippers with tall platform soles that could elevate the wearer 4-10″ or more in height.

The women below are pictured with some of the prominent accessories of the 17th Century. These include folding fans, and soft facial masks.

The women below are pictured with some of the prominent accessories of the 17th Century. These include folding fans, and soft facial masks.

The woman on the left also has a mantilla-like veil covering her face. The mantilla is a Spanish fashion, while these women are Dutch. Since both regions of Europe tended to favor conservative ideas, it is not surprising that they might influence each other.

QUICK REVIEW

TYPE OF DRESS: tailored. Stuffing disappears creating a softer silhouette.

TEXTILES: Same available textiles as previous period: wool, silk, cotton and linen. More fragile and complex fabrics and elaborate patterns are worn among supporters of the royal throne. Sturdier, utilitarian and plainer fabrics were worn among the Puritan groups.

SILHOUETTE SHAPE: Much less horizontal and somewhat wilted or deflated compared to the previous period. Waistlines for both men and women float upwards and skirt understructures disappear. Women’s forearms are exposed for the first time in centuries. Everything is heavily trimmed in lace, ribbon, braid.

BASIC GARMENTS: Men: Shirts, falling ruff/band, doublet, capes, boots, boot hose, cavalier-style and capotain hats. Women: chemise, stays with busk, petticoat, bodice & shirt OR gown, stomacher, fichu, pelerine.

MOTIVATIONS FOR DRESS: Status as it relates to politics and religion. People start to align along the puritan or royalist spectrum. Within that alignment wealth is shown differently. Puritans show wealth through quality of fabric and limited lace/trim usage. Royalists use finer and embellished fabrics and exhibit exuberant decoration.

KEY IDENTIFIERS: Elevated waist, looser & less structured (deflated) garments, lots of lace & decoration, cavalier-style hats, captains, visible forearms on women, large collars (pelerines & fischus), boots and capes, female ‘dog ear’ hair style.

Recent Comments