The Georgian Period

Contemporary Events

- Louis XIV passes in 1715. His great-grandson, Louis XV, becomes the King of France at the age of 5. France enters into a Regency period until the king comes of age and is able to reign. Unfortunately, this task was not one of his strengths. Bored with his duties as king, he found entertainment through hunting and women. The most famous of his mistresses was Madame de Pompadour. She was a very influential patron of the arts and often served as the King’s political advisor.

- Louis XV’s reign ends with his death in 1774. His grandson, Louis XVI succeeds him. His wife, Marie Antoinette was a young Austrian princess. During her first years as queen (she married Louis when she was 14), she proved to be immature and frivolous. She also favored Austrian customs over the French. These traits lead to an intense dislike for the Queen among the older nobles.

- 1776: The American Revolution successfully separated the “New World” from English ties. France helped finance the Revolution, these events encouraged Frenchmen desiring to reform French politics.

- Writers, nicknamed philosophes, promoted the idea that through reason and science rather than the perceived abuses of French court life and government a better world could result.

- 1719 and 1748: excavations in Italy uncovered the ruins of two Roman cities near Naples–Pompeii and Herculaneum. These cities had been destroyed by the eruption of Mt.Vesuvius in 79AD. Discovery of these nearly perfectly preserved cities revived interest in “classical” (ancient Greek and Roman) life. This will usher in a renaissance of sorts with Neo-classical art and architecture leading the way. Dress will not be influenced until after the French Revolution concludes.

- England enters the Georgian era. The century begins with Queen Anne’s (daughter of James II) brief reign. She is followed by George I, II, and III.

Early Rococo (Georgian) Male Dress-18th Century

A young man’s/older boy’s coat and breeches, 1705-15, English; Red wool, silver embroidery, mended 1710-20, altered 1852. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, England

This red wool suit is dated between 1700-1705. It is embroidered with silver-gilt thread.

The suit coat (AKA surtout or justacorps) of the Georgian period evolved from that of the Restoration period. They show slightly more shaping through the torso than their predecessors, and skirts will gradually get wider and fuller.

Other notable characteristics are:

-They initially remain collarless.

-Sleeves are shortened-ending somewhere between the wrist and elbow. Sleeves often finish in a large cuff, though there were also cuffless varieties.

-This particular coat is rather short. The typical coat is just short of knee length.

-Coats have the ability to button from neckline to hem.

–Pocket placement is rising to functional levels. No more are pocket flaps floating just above the hem of the jacket.

–Breeches are moderately full through the rump, but are narrow through the leg. Breeches develope a fall front–a square flap that buttons closed.

His cravat is tied around his neck with the ends hanging loosely.

“This coat and waistcoat illustrate formal daywear for men in the 1740s. The fabric of the coat is a rich shot green and black silk. By the 1740s the waistcoat is shorter in length than the coat. It is made of yellow silk brocaded with coloured silk and silver threads. Comprised of large flowers and leaves densely covering the fabric, the brocaded pattern is typical of Late Baroque design. The coat is collarless. It fits tightly to the body, but has very full skirts pleated to the sides at the hip. The sleeve cuffs are wide, reaching about half way to the elbow. Typical of the early 18th century, the waistcoat is also sleeved, although this style was beginning to go out of fashion by the 1740s.” Victoria & Albert Museum, 1745

The brown coat above is characteristic of those from around 1720-1740s. It is made of silk and features a ornately embroidered waistcoat (which is also made of silk). You can read what the V & A has catalogued about the suit in the caption above.

After this time:

-the skirt of the coat continues to widen. Excess fullness is controlled by pleating it into the center back and sides of the coat.

-Coats are now only able to button from neckline to waist. The center front corners of the coat are slightly angled toward the back, preventing the coat from closing below the waist.

18th Century Color Plates from English Costume 1066-1820

For a brief time after 1720, it becomes fashionable for the wide skirts of the coats to be stiffened with buckram, a heavily sized fabric of cotton or linen. This stiffening gave the affect of the skirt standing away from the body. This attempt to compete with the growing size of the female silhouette is shortly lived. In the second half of the century the silhouette will again grow narrow and vertical.

This man’s coat is made with boot cuffs–large cuffs reaching up to (or beyond) the elbow). Notice how short his sleeves are and the placement of his pockets.

He is carrying a tricorne hat underneath his left arm (it is red and purple).

Coats of the first half of the 18th Century generally had side vents to accomodate the wearing of a dress sword (a sword worn solely for decoration by the aristocratic class. It is truly jewelry and would rarely be used for fighting or defense). It is possible for the coat to also have a center back vent in addition to the side vents.

Notice that his shoes have red heels. This remains a popular fad among the wealthy/noble classes. Tongues of shoes may also be painted red.

Waistcoats during the first half of the 18th century may or may not be sleeved. They continue to be long, and are cut with added fullness (just like the coat). They are slightly shorter than in the previous century–falling about 4″ short of the coat hem.

This ensemble features a cravat tightly wound around his neck. The frill emerging from the center front of his waistcoat is a jabot. It is attached to his shirt.

Portrait of Francois-Marie Arouet by Nicolas de Largillière, c. 1724. Arouet’s “nom de plume” was Voltaire.

White linen cravats remain the neckwear of choice for men in the first third of the 18th century. The typical cravat was approximately 4 feet long and 6 inches wide. It wraps around the neck several times, concealing the neck band of the shirt completely.

The way that a man chose to tie his cravat was indicative of his personal style and creativity. However, there are a number of cravat tying variations that received specific names after being worn by their creator.

In the Largilliere portrait at the left, Voltaire wears his cravat in a manner referred to as a steinkirk. The ends of the cravat are twisted together in a rope like manner. The key identifying feature of this trend was the pulling of one end of the cravat through a buttonhole in his waistcoat.

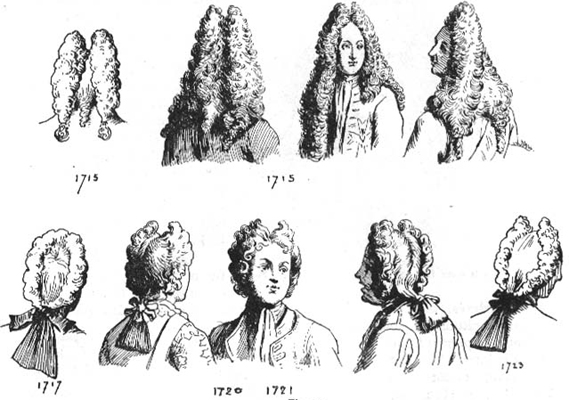

Below are some of the popular wig styles for men in the first half of the 18th Century.

Wig fashions from 1715-1725 early in the reign of Louis XV. Images from Diderot’s Encyclopedia, c.1762

The Full Bottomed Wig (top row: 1715) was introduced in the 17th Century by Louis XIV. It lingers in the early 18th Century-first as a fashionable wig, and then as a choice for the more conservative man. Ponytail wigs-known as wigs with queues (ponytails or braids) that stood tall off the forehead with strategic back combing were called toupee/foretop wigs (bottom row). These were introduced in the 1710s. The final variation here is called a bag wig since the queue is placed into a silk bag. Despite the introduction of the toupee wig, most wigs for men favor tall and wide styles during this part of the century. As the suit silhouette grows narrower and more vertical, wig styles follow suit. Wigs may be powdered.

Late Rococo (Georgian) Male Dress-18th Century

Men’s three piece suit, around 1760 Fashion, 18th century. Men’s three piece suit, around 1760. Getty Images.

This suit dates to the 1760s. All three components-coat, waistcoat, breeches–are made of the same fabric. Suits of this nature are referred to as ditto suits.

Beginning mid century, the amount of fullness in the coat begins to decrease. Initially, pleating at center back and the sides disappears. Gradually, the cut of the coat changes as well. Beginning at about mid chest, the center front corners of the coat are completely rounded off (or “cut away”) and slope backwards. These coats generally feature buttons from neckline to hem, but only the top 2-3 buttons are actually able to function while being worn. The rest of the buttons and buttonholes were merely decorative.

As a result of the new cutaway styles, much more of the waistcoat and breeches are able to be displayed. These garments begin to take on a greater importance in the overall ensemble.

Coat sleeves begin to lengthen again, and will eventually reach the wrist once more.

With this style of coat, the waistcoat becomes much shorter. The one pictured with the Ditto suit above reaches to the low hip.

Breeches will become more narrow and more fitted as we approach the end of the century.

Formal ensemble, 1790-1800 (made). Museum Number T.148 to B-1924. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England.

The blue full dress suit at the right is from the 1790s. The design of the garments is in place earlier, however. Many characteristics of men’s suits from the last 1/4 of the century are shown here.

The standing collar developes late in the 1760s. The cutaway center front becomes more and more exaggerated. It is no longer possible for the coat to button closed. Also, the fullness through the skirts disappears altogether. There is most likely only one vent (at center back) in this coat. Sleeve length has returned to the wrist.

Breeches are very narrow and fitted to the leg. Leather breeches become favorable during this time, since they were able to conform to the leg of the wearer and maintain a smooth fit. (The breeches shown here are not leather.)

The waistcoat shortens drastically. The hem usually falls somewhere between the high hip and waist. They are nearly always sleeveless now, and resemble a modern day vest.

The male calf emerging from the tight breeches is considered an erogenious zone during the second half of the century. The fashionable male was well aware of this. He may even chose to wear artificial calves in order to make his leg apear more shapely.

Portrait of Friedrich II of Prussia (who ruled 1712-1786). 1745

This gentleman wears the new neckwear of choice: the stock and soliatire.

The cravat slowly fades from popularity-being retained by the more conservatively fashioned individuals. The new alternative (the stock) featured a linen square (lined in buckram) folded to create a tall, stiff neckband. The stock concealed the neckband of the shirt, and fastened at the center back with a buckle, buttons, or ties. A solitaire– a dark (usually black) silk scarf (about the size of a modern handkercheif) or a black ribbon (tied in a bow)-was worn on top of the stock.

This gentleman also wears the new popular hat over his wig. As wig styles become less voluminous, hats can actually be worn on the head once again. The tricorne hat is the favored headdress. It is created by folding up the brim of the previous century’s cavalier style hat, creating three points.

Gentlemen who still favored larger styles of wigs might find it difficult to balance a hat in addition to the wig. He would have a highly decorated flattened style of hat designed to be carried rather than worn. This hat was named chapeau bras, which translates as “arm Hat”.

Philadelphia Museum of Art – Geography: Made in United States, North and Central America Date: c. 1775-1785

These two coats are both dated from the 1790s. They are similar in all manners of construction* to the previous blue coat (from the V & A) save the elaborate embroidery. All three coats might be owned by the same upper class gentleman.

Men’s wear begins to favor simpler styles in the second half of the century. Quaker built, “plain dress” attire becomes the staple for daytime attire, while the more extravagant attire is saved for the most formal evening occasions or “Court Dress”. Men begin to favor quality of cut and construction over ornate decoration as a sign of wealth.

The coat on the left does seem to have a turned down collar, making it slightly different than the one on the right. Turn down collars come into fashion during the 1770s, and fold back lapels (as we know them today) come into fashion during the 1780s. Both of these collar constructions are influences from the “country dress” Frock Coat.

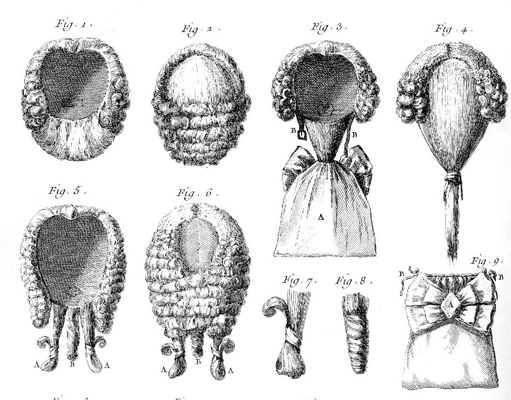

Pictured here are various Wig Styles for men seen during the second half of the 18th Century.

Male Wigs of the Late 18th Century. Images from Diderot’s Encyclopedia, c.1762

Top Row: Left/Center Left(Fig. 1&2): Bob Wig, Far Right (Fig. 4): Toupee/Fortop Wig with queue, Center Right (Fig. 3): Bag Wig.

Bottom Row: Left/Center Left (Fig. 5&6): A Bob Wig Variation, Far Right (Fig. 9): Silk bag from Bag Wig.

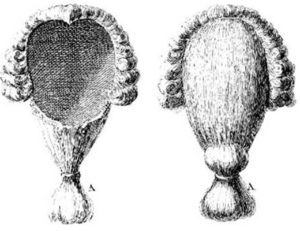

This is a Club Wig also known as a Catogan, which is rather similar to the Toupee/Foretop wig. The queue is extra long. It is double backed upon itself and secured in the middle with a ribbon. This creates a ‘figure 8’ or hourglass shape (A) that hangs like a heavy knob or a ‘club’ in the back.

This is a Club Wig also known as a Catogan, which is rather similar to the Toupee/Foretop wig. The queue is extra long. It is double backed upon itself and secured in the middle with a ribbon. This creates a ‘figure 8’ or hourglass shape (A) that hangs like a heavy knob or a ‘club’ in the back.

Rococo (Georgian) Female Undergarments

As has been the case for many centuries, the first thing a woman would put on when getting dressed would be her chemise. The 18th century chemise featured a wide, low neckline edged in lace and sleeves that ended just below the elbow. Little of the chemise would show when the lady was completely dressed-perhaps only the lacey edges of her neckline and sleeves.

As has been the case for many centuries, the first thing a woman would put on when getting dressed would be her chemise. The 18th century chemise featured a wide, low neckline edged in lace and sleeves that ended just below the elbow. Little of the chemise would show when the lady was completely dressed-perhaps only the lacey edges of her neckline and sleeves.

She would next put on her petticoat, which an 18th century lady may refer to as a ‘coat’ or a ‘dicky’. Petticoats of this century are narrower than previous century. They exist for mainly utilitarian needs-warmth, protection from the pannier/panier contraptions of the day, and modesty. A woman could possibly have day and evening versions of this garment. Her evening petticoat would be more elaborately decorated than the one worn for everyday.

She would next put on her corset/stays. 18th century corsets were worn from pre-pubescent childhood and onward as a form of ‘waist training’. A fashionable woman had a very small waist. Beginning to wear the corset when one’s body was still developing helped to control the size of the waist. Corsets of this century were engineered to accentuate a round full bust, and create the tiniest waist possible. Busts may also be padded in order to enhance this effect. The shoulder straps were attached to the back of the corset and tied in front. These could be loosened or tightened in order to provide added lift to the bustline. 18th century corsets also are generally tabbed at the waist, providing a smooth, flattering transition between the waist and hip area.

She may or may not wear drawers underneath her petticoat. Some sources suggest that French women could have chosen to wear them, other sources say English women certainly did not. The jury is out on this matter.

This corset is covered in ‘dress’ material. It would have a matching skirt and sleeves. Some corsets sometimes served double duty as the bodice as well. In this case, an additional corset was NOT worn.

This corset is covered in ‘dress’ material. It would have a matching skirt and sleeves. Some corsets sometimes served double duty as the bodice as well. In this case, an additional corset was NOT worn.

The armscye would feature a series of closely set eyelets (holes finished off like a buttonhole through which laces passed. The CF lacing of stays also employs eyelets) which allowed sleeves to be laced on and off. Notice the armscye placement in this corset which results in a very narrow back. Pulling the arms slightly backwards (as this corset would inevitably do) helped to thrust the bustline forward, thus accentuating it.

Most dresses of the 18th century feature a stomacher of some sort. This one is unusual because it falls under the laces rather than concealing them. The stomacher (and decoration of it) helped to create the illusion of a smaller waist by drawing attention to the two converging lines that make up the edges of the triangle.

Notice how stiff this garment is. It virtually supports itself. Bones are literally placed side by side-ensuring maximum control of the flesh underneath and a smooth appearance for the bodice outside.

“Tight Lacing, or Fashion before Ease,” by Bowles and Carver after John Collet, London, England, ca. 1770–1775. From the collections of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Corsets are laced tighter in this century than they ever have been before. Tight lacing, which begins its practice in this century, becomes a much discussed fashion trend in regards to women’s health and longevity during the next century.

(It must be noted that Victorian age women find a way to lace their corsets even tighter than the Georgians due to the invention of metal eyelets. These prevented the tearing of the fabric that often resulted from the strain put upon them by the laces).

This image shows us some of the realities of properly adorning an 18th century lady.

First, she would be unable to dress herself, for she could not reach the ties of her corset.

Second, quite a bit of strength was required in order to acheive a fashionably sized waistline.

Third, from the look on her face, it was quite unlikely that this was a comfortable manner of dressing one’s self.

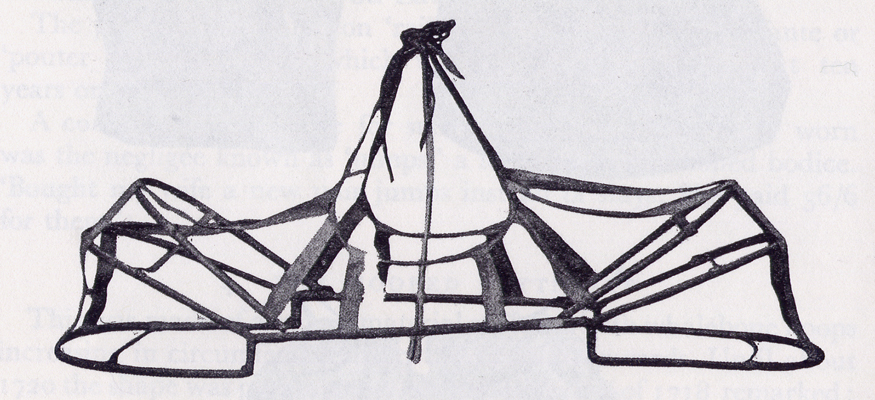

Hoops return with a vengeance in the 18th century. The names ‘farthingale’ and ‘verdugale’ have disappeared from use, but initially the contraption features the same technology. The hoop skirt sees quite an evolution over the century.

Hoops return with a vengeance in the 18th century. The names ‘farthingale’ and ‘verdugale’ have disappeared from use, but initially the contraption features the same technology. The hoop skirt sees quite an evolution over the century.

Beginning in 1710-hooped petticoats resembled the Spanish Farthingale or verdugale. They featured hoops of increasing size made of whalebone and sewn into a petticoat of sturdy fabric creating a cone shape.

During the 1720s– the silhouette grows and becomes more rounded. Hooped skirts have a dome-like appearance such as the hoop skirt illustrated here at the right.

During the 1730s, the preferred silhouette flattens in the front and back and remains wide from side to side. This is acheived by a series of tapes inside the hoop skirt. When the tapes were tied, they pulled the front and back together. The shape is reminiscent of the ellipse silhouette of the Spanish guadinfante.

During the 1730s, the preferred silhouette flattens in the front and back and remains wide from side to side. This is acheived by a series of tapes inside the hoop skirt. When the tapes were tied, they pulled the front and back together. The shape is reminiscent of the ellipse silhouette of the Spanish guadinfante.

As this illustration demonstrates, these things were quite cumbersome and awkward. They made every day activities a bit difficult. In order to pass through a doorway, the wearer would have to either slide through sideways or attempt to flatten them (as the woman at the left in the above image is attempting to do). As you can probably imagine, the latter method could hardly be acheived gracefully. It is a good thing that she is wearing a petticoat!

French Panier, typically worn under dresses to gain width

The wide silhouette reaches its maximum width in the 1740s and remains in favor for much of the century-until about 1775 (after this point they linger only in Court Dress for the rest of the century).

New solutions were continually sought to facilitate life for the wearer. This version is from about 1750 and is made of wood. It was easier to walk in than the previous ‘squashed hoop’ version (due to the lack of tapes around the legs), but there was still the problem of passing through doorways, since fashion is able to change much faster than architechture.

The solution to the doorway problem leads to the invention of the panier/pannier (called ‘false hips’ during the 18th Century). A panier was a hooped bustle-like contraption. Two were worn–one on each hip. They featured hoops set into fabric and collapsed under the arm when lifted upwards. The word ‘panier’ is french for ‘basket.’ Victorians gave the false hip the name panier, because it looks like the wearer has a basket sitting on each hip.

The solution to the doorway problem leads to the invention of the panier/pannier (called ‘false hips’ during the 18th Century). A panier was a hooped bustle-like contraption. Two were worn–one on each hip. They featured hoops set into fabric and collapsed under the arm when lifted upwards. The word ‘panier’ is french for ‘basket.’ Victorians gave the false hip the name panier, because it looks like the wearer has a basket sitting on each hip.

Today, it is common to refer to this silhouette as “panier” regardless of what version of support contraption is is worn.

There were also habit-shirts. A habit-shirt was a cotton or linen blouse modeled off of a man’s shirt. It was worn over the corset with a lady’s horseback riding costume-called a habit or redingote. During the second half of the century there was a fad for dresses based on riding attire called redingote dresses/gowns. A redingote dress would never actually be worn while on the back of a horse, in fact many of the ladies wearing this fad did not even know how to mount a horse. These later fashions reflect the influence of ‘country’ attire on daily dress and would not truly function in the same manner as a habit. However, the habit-shirt would still be worn with the trendier version of this costume. These blouses foreshadow the shirtwaist blouse which will find wide spread popularity in the next century.

Early Rococo (Georgian) Female Dress – (1700-1730)

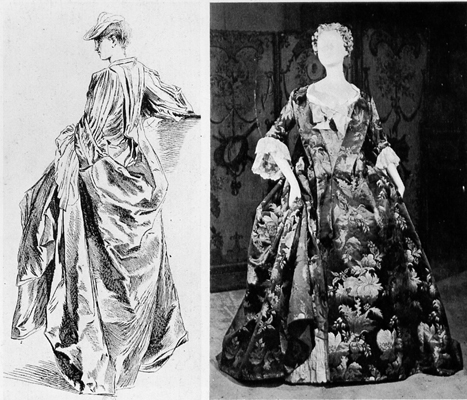

1729 Fashion Plate of a Robe Volante (Sacque gown)

Extant Blue Silk Robe Volante. C. 1730. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Worn with the revived hooped petticoats (cone and dome shaped) of the early 18th Century, the new fashionable cut of gown is the sacque gown (Also known as robe battante, robe volante, innocente OR a flying gown).

This dress appears to hang straight and loose from the shoulders, flowing loosely around the body. Fullness in the back is gathered or pleated into the neckline, creating a “waterfall” of fabric referred to as the back drape.

These gowns were often worn over a decorative corset and/or stomacher and a decorative petticoat (which may or may not be seen).

Silhouettes of this style are wide in all directions, due to the roundness of the hoop shape.

Figure on left is from Figures de differences caracteres by Watteau. c. 1715 Both images show early evolution away from the Robe Volante and toward the Robe a la Francaise.

The sacque gown above and to the right reveal the decorative stomacher center front. They are worn with a much smaller hoop than the one pictured at the top of the page. There is much variation in silhouette size due to personal taste and fashion aesthetic.

The sacque evolves into the gown that is given the name robe a la francaise. This dress becomes known as a Watteau gown by modern historians due to Jean-Antoine Watteau’s prolific use of them as subjects in his painting).

The gowns above date between the previous images and the painting below. It shows evolution in progress. Notice that the back drape is maintained, and there is added shaping through the torso.

Mid Rococo (Georgian) Female Dress – (1730-1760)

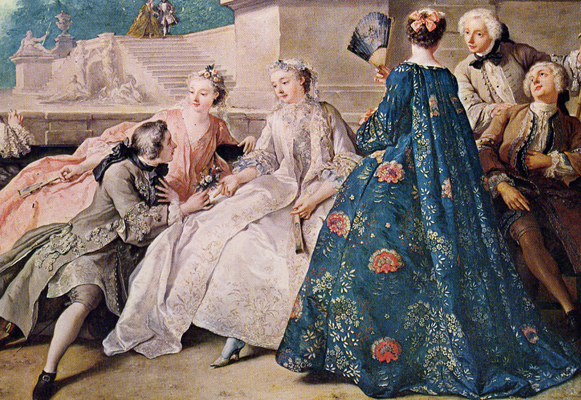

Declaration of Love painted by Jean Francois de Troy. 1731. Brandenburg National Gallery of Art.

Here we see the robe a la francaise (in blue) in all of its glory. This painting shows us both the sacque (in white & pink) and the new style (in blue).

The “french gown” is usually worn with some variation of the wide pannier/panier style support contraption. The silhouette becomes wide from side to side, and narrow from front to back. The back drape is maintained and the bodice is heavily structured (even underneath the drape in back).

During the middle Georgian period floor length trained dresses seem to be the most common. Dress sleeves usually end at or just below the elbow-often practically foaming with lacy ruffles (called engageantes).

Hairstyles are still fairly simple-braided and coiled on top of the head. Hair tends to be worn ‘up’ rather than down. Notice that there is already the tendancy to accessorize the hair. The woman in white wears a small mob cap or pinner (a lacy mob cap about the size of one’s hand) in her hair, while the woman in blue wears a smart little bow at the back.

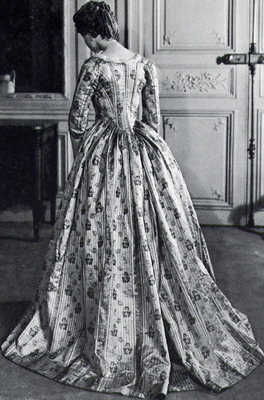

The robe à l’anglaise was a dress “consisting of a bodice cut in one piece with an overskirt that was parted in front to reveal a matching petticoat. Its fitted bodice did not have the center back pleats, often referred to as the “Watteau back,” that typified the equally popular style of the robe à la française.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbronn Timeline of Art History.

The alternative to the wide silhouette of the robe a la francaise was the robe a l’anglaise. This gown is rarely worn with pannier/panier style hoops. Instead, a false rump or bumroll may be used. This gown usually features a waistline that dips in both the center front and the center back. The skirt is usually quite full and pleated or gathered into the waistline. It, too, often has a train and sleeves that burst in engageants.

As the name suggests, this gown was more popular with the English and Americans, while the previous style was more popular with the French. However, it was quite possible–and likely probable–that a lady of the mid 18th Century would have both styles of gowns at her disposal. The “English gown”, for obvious reasons, was much more suited for everyday living. However, formal versions of this gown did exist during this middle period for court dress.

Favored dress materials differed from France to England as well. French women loved fine silks, while English women loved painted and printed cottons.

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Caracao or Casaquin bodices c. 1786

In addition to the various gowns already mentioned, women had some bodice & skirt combination options as well.

Pictured here is the caracao or casaquin. This was a fitted jacket-like bodice. It generally features a peplum that ends at the low hips. Sleeve length ranges from wrist to 3/4 length. These jackets may be made to match or contrast with a decorative petticoat.

As a rule, the more the fabrics of an ensemble coordinate (meaning parts are made of the same fabric) the more formal the ensemble was regarded.

Portrait of Madame de Pompadour (1756), detail. François Boucher (French, 1703-1770). Oil on canvas.

The painting below depicts a rather pensive image of Madame de Pompadour.

She wears an elaborate collarette fashioned of fabric (probably silk) roses. The term ‘collarette’ refers to almost any choker-like necklace. These may range from a simple piece of ribbon tied in a bow, ruffles worn like a small falling ruff, or even fabric roses. The low decolletage of the 18th Century gown heightens the importance of jewelry and accessessories such as this.

Her stomacher is decorated with ribbon eschelles (a series of graduated ribbon bows that are attached to the stomacher with the largest bow on top and the smallest on the bottom). This arrangement helped to accentuate the desired small waist. Stomacher and corset decoration nearly always had this goal in mind.

Finally, we are able to catch a glimpse of her engageantes, the ruffles are literally spilling out of the sides the painting. These sleeve ruffles could feature 1, 2, 3, or more layers of lace. The othermost layer was sometimes made of the gown fabric instead of lace. These ruffles are attached to the gown rather than the chemise (though the chemise sleeve generally ended in a small ruffle as well…adding to the frothiness).

The neckline of Mme. Pompadour’s gown is very common during the Georgian period. Left from the Mantua gown of the Restoration period, the bodice has a “jacket-like” appearance with the stomacher filling the space between.

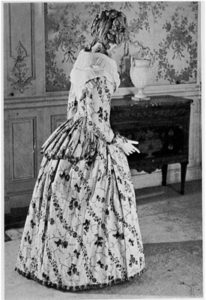

Late Rococo (Georgian) Female Dress – (1760-1795)

Late 18th Century women’s clothing is greatly influenced by the passing of leisure time “in the country.” Women start to appreciate looks that are, in their eyes, more “natural.” This applies mostly to the clothes themselves, and not necessarily hair and headdress. While clothing styles are “simplifying,” hair styles continue to expand, reaching their largest altitudes (12-18″ tall) during the 1770s.

Late 18th Century Fashion Plate

“Country” influences include:

-Shortened skirts (ending just shy of the ankle)

-Skirts of gowns looped, draped, and pulled to the back

-Narrower paniers and/or sole reliance on the false rump as an understructure. Wide paniers were saved for court dress.

-Mob cap variations worn as headdress outside the boudoir.

-Wide brimmed, low crowned bergere/shepardess hats.

-More frequent use of bodice & skirt or gown & non-matching petticoat ensembles (like the girl in brown at the right).

Fashion Plate 1776 showing a robe a la polonaise.

There are hundreds of variations as to how a lady might drape and bustle her skirt. This gown is worn a la polonaise. The overdress is drawn up and puffed out into three distinct swags to show off the decorated petticoat. An intricate system of tapes and rings would be attached underneath the skirt in order to create and control the puffing.

Another new ‘natural’ style is the chemise a la reine (Queen’s chemise). This fashion surfaces around 1781, after Marie-Antoinette was spotted wearing a gown in the style of her chemise in her garden. This gown is initially characterized as a light weight gown of white muslin cut all-in-one from shoulder to hem. It generally has a wide neckline, and is drawn in at the waist with a sash. Its popularity marks a revolt against the heavily boned bodices that typify this century.

Portrait of Dona Tadea Arias de Enriquez by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes. 1793

Eventually this style is made in other colors (usually pastel) and regains a bit of the stiffness that characterizes other gowns of this century. It does, however, truly foreshadow the fashions that will dominate the early 19th Century.

This woman’s hairstyle is a new “natural” alternative to the architectural coiffures of her day. The hair is cut, curled, and back combed, creating (to modern eyes) a style similar to an “Afro.” This look is named the hedgehog hairstyle. Though this look employs hair’s natural tendencies, the style remains tall and wide.

Illustration by Sigmund Freudenberger published in Tableaux de la Vie in 1789.

In court dress, the panier/pannier silhouette remains at its widest for remainder of the period. Large paniers become considered the most formal mode of dress. While the everyday silhouette narrows, the formal one seems to get wider. Women dressed at court appeared both doll-like and cake-like, creating quite a presence.

French Hairdress of the 1770’s. Museo Stibbert, Florence, Italy

Hair reaches its maximum height in the 1770s. It is a towering structure adorned with feathers, jewels, birds, ribbons, and just about anything a lady could perch on top of her head. Women (with the help of some really creative hair dressers) supplemented their own hair with pads (rats) and false hair building the hair up and creating gravity defying up sweeps. Heads carried boats, horns of plenty, entire menageries, scale landscape gardens, and fresh flowers tucked into vials of water hidden in the hair (these were considered sublime simplicity).

They did not stop at the hair. Hats were often just as large, just as decorated, and miraculously balanced on top of the towering hairdo.

French Hairdress of the 1770’s. Museo Stibbert, Florence, Italy

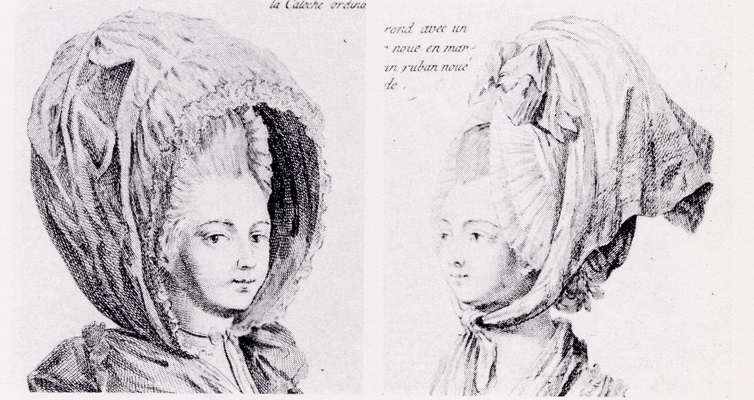

Calashe Hood. 1780.

Once a lady had her hair done, she would keep it in place for quite some time. It was necessary to protect her ‘masterpeice’ from the wind and the weather. Ladies also desired to keep the sun off their skin (maintaining the desired paleness). The calashe hood was a large hood with hoops, that when raised would shelter the large coiffure from the elements. It then could be lowered and collapsed upon itself in a manner similar to the roof of a convertable car.

QUICK REVIEW

TYPE OF DRESS: Tailored.

TEXTILES: textile colors shift away from heavy & darker colors of the Baroque period to a lighter color palette. There is an overall sense of lightness to much of the Rococo period. Decoration tends to be applied to garments: embroidery, quilting, ruffles, ribbons, etc. All over floral patterns are very popular–brocades, damasks, satins, taffetas, printed cottons in pastels and floral tones. Wool continues to be associated with modest dress and outerwear (things worn for warmth). Buckram (a sturdy plain weave cotton stiffened with glue or starch) finds use in coat linings and headdress.

SILHOUETTE SHAPE: Male silhouette is rather feminine: soft shoulders, small waists, full skirts on coats. Initially hourglass and will transition to columnar. Female silhouette favors a slight torso, while unnaturally wide side to side (not front to back) due to use of panniers and/or bumrolls. Collarbone, neck, cleavage, forearms exposed. Excessive decoration applied much like frosting on a wedding cake. Erogenous zone is the calves. It would be improper for ladies to show them, and men will pad them for a more shapely leg.

BASIC GARMENTS: Men: 3-piece suit (suit coat, waistcoat, breeches) worn with a shirt and cravat OR stock & solitaire. Wigs remain popular for men. Women: chemise, stays, panniers, stockings, shoes, petticoat, gown or bodice & skirt, huge hair, stockings, shoes,

MOTIVATIONS FOR DRESS: Status: display of wealth. France: follows liberal fashion (soft delicate fabrics, pastel colors, silks, brocades, velvets, embellished fabrics etc). America/England: heavily influenced by the effects of puritanism (cottons, wools, printed fabrics).

KEY IDENTIFIERS: tricorne hate, wigs on men, 3 piece suit (wide skirt with long waistcoat during first half, grasshopper style with short waistcoat during second half), coats unable to button to hem, pockets move upward to a natural placement, narrow breeches, female silhouette has diminished torso but excessively wide skirt, pannier silhouette with frosting-like decoration, huge elaborate headdress (not wigs), heavily powdered make-up, powdered hair/wigs, bright colors/pastels favoring motifs inspired by nature.

Recent Comments