The Gothic Period (Medieval)

Contemporary Events

- The last Carolingian King was deposed in 888. No power strong enough to keep the empire together emerged. Invasions from Magyars, Saracens, Arab raiders, Vikings and others ransacked the area leading to the ruin and depopulation of many areas.

- Out of the chaos feudal monarchies begin to emerge. Leaders gathered around them trained fighting men (armored knights on horseback thanks to the invention of the stirrup). Vassals were granted a fief by the Lord in exchange for military services. Serfs worked the land for the lords and knights. The Lord owned all the land in his kingdom, allowing the vassals and serfs to live there in exchange for loyalty, protection and service. Castles were built on these lands as places of protection and homes for the Lord and his family.

- By the 12th Century castles had evolved from crude structures made of wood to elaborate stone structures.

- Feudalism takes different forms across Europe. England was the last to develop a feudal culture. Duke William of Normandy invaded England in 1066, made himself king, and established feudal life on the island.

- Beginning in the 11th Century, under the encouragement of Pope Urban II, seven christian crusades were waged against the Moslems. The intention was to free the holy places of Christendom from their current controllers (the Moslems).

- By the 13th Century, many new products (discovered during the Crusades) were imported into Europe including new foods, spices, drugs, works of art, and fabrics (silk damask is particularly desired). Cotton (from China) is introduced as a new fabric–with it comes muslin and dimity.

- Feudalism begins to wane before the 14th Century as Kings find new revenue from taxing cities and towns. Serfs become free peasants who must now pay rent and taxes, but have the freedom to move between cities and kingdoms. They move in large groups from the countryside to the cities.

- A plague nicknamed The Black Death struck Europe beginning in 1347 and striking throughout the 14th & 15th Centuries killing a 1/3 of the population.

- Gun powder is invented in the 15th Century, changing the face of warfare again.

Early Gothic-13th & 14th Centuries

The Palais de la Cité and Sainte-Chapelle, viewed from the Left Bank, from the THE BELLES HEURES DE JEUN, DUKE OF BERRY: St Paul the Hermit, 1410-16. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

These peasant women wear chemises (white) and cotes. They have veils draped and wrapped around their hair. The peasant men in the background are wearing braiesand chemises and possibly cotes. They have hats on to shield themselves from the sun.

The peasant man on the right wears a cote with a magyar or dolman sleeve.

Harvesting barley in a long, belted, shirt-like garment. Late 1300’s. From 20,000 YEARS OF FASHION, by F. Boucher, p. 199.

This sleeve is fitted from elbow to wrist and gently curves into the torso under the arm instead of creating the right angle that is typical with a “T-shaped” garment. This new cut of sleeve provided an added ease of movement and prolonged the life of the garment.

Notice that even the peasants are wearing pointed shoes.

Plate 19c THE HISTORY OF COSTUME By Braun & Schneider.

This image shows us many of the key differences between the male surcote and the cote-hardie. The surcote is fitted through the torso, with a moderately full skirt. It is worn over a cote with fitted sleeves. We see the cote revealed under the surcote sleeve which features a short tippet.

The cote-hardie is a shorter garment that opens center front and closes with buttons. It is thought to have evolved from the surcote. The cote-hardie generally has a short skirt that is attached at a dropped waist seam (hidden by his belt here).

It becomes difficult in the next period to distinguish the cote-hardie from the garment called the doublet/pourpoint/gipon. At this time, the doublet/pourpoint/gipon seems to refer to a sleeved, quilted and/or fur lined garment that is worn between the chemise and cote-hardie for warmth.

THE BELLES HEURES OF JEAN, DUKE OF BERRY: St Paul the Hermit 1410-16. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Another new garment for men and women is the houppelande (worn by the man at the right). It was a long and full garment that is somewhat associated with the garnache and herigaut.

The houppelande is fairly fitted through the shoulders and drops into a full, unshaped garment below the shoulders. It is generally belted at the natural waist or at the hip-line. It often features a standing collar (carcaille) and some form of decorative sleeve: bagpipe, pendant, or a variety of hanging sleeve. Here we see a large pendant sleeve with dagged edges.

He is wearing a chaperon on his head in the turban-like new chaperon style.

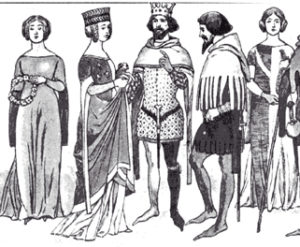

This drawing to the left portrays many of the key identifiers for the 13th/14th Centuries.

This drawing to the left portrays many of the key identifiers for the 13th/14th Centuries.

1. tippets on sleeves (trailing streamer-like extensions –either part of the sleeves or detachable)

2. dagged edged chaperon

3. the use of buttons (the crowned man wearing the cote-hardie in the center of the image has many down his center front closure)

4. the practice of parti-coloring

5. pointed shoes and pedules (hose with attached soles)

1. Woman in the dress of the beginning of the 14th Century. (Quicherat)

6. the ram’s horn hairstyle on the women

This lady lifts the skirt of her surcote to reveal the hem of her cote and pointed shoes. She is wearing the ram’s horn hairstyle, but has draped her wimple over the braided buns to conceal them.

She would also be wearing a chemise and hose.

There is a variety of options in the realm of fashionable feminine dress during the Gothic period. Personal aesthetics, combined with disposible income, resulted in a greater occurrence of individualized fashion.

There is a variety of options in the realm of fashionable feminine dress during the Gothic period. Personal aesthetics, combined with disposible income, resulted in a greater occurrence of individualized fashion.

All three of these women wear variations of the cote and surcote.

The lady on the fair left is wearing the version of the surcote, sometimes referred to as a “sideless gown.” Introduced late in the 13th century, this style becomes quite popular by the time we reach the second half of the 14th century. The deep armholes are sometimes referred to as the “windows of hell.” This refers to the fact that the female form is only obscured by a tightly laced cote.

The woman in the center wears a basic cote & surcote combination (similar to the one pictured above). The surcote here is rather unfitted.

The woman on the right wears a fairly fitted surcote that prominently features fitchets (slits through which the hand could pass to access an alms purse or pouch attached to a belt underneath) and tippets. All three of these styles coexisted.

At some point duirng the 14th century female cote/surcote also takes the name gown or kirtle. All three terms are acceptable. It would still common to wear an under gown and a over gown, however, regardless of what name you give them.

At some point duirng the 14th century female cote/surcote also takes the name gown or kirtle. All three terms are acceptable. It would still common to wear an under gown and a over gown, however, regardless of what name you give them.

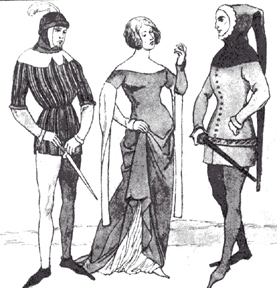

The men in this image wear cote-hardie variations. The man on the left is showing the sleeves of his pourpoint (AKA doublet) on his forearm. The parti-colored hose are most likely tied to their pourpoints with laces (AKA points).

“Points” is a Middle Ages term that refers to the metal tip (an aiglette) that is used to finish the end of a lace. FYI, the piece of plastic that finishes a modern shoe is still called an aiglette.

The man on the right wears a chaperon with a long liripipe.

Late Gothic – 15th Century (Northern Europe)

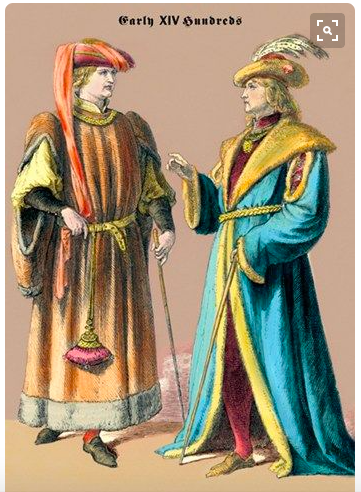

THE HISTORY OF COSTUME, Braun & Schneider

These gentlemen both wear houppelandes that exhibit new fashion trends of the 15th century. Both men have slashings in their sleeves. The man on the left has a practical/functional slashing through which his arm may pass, while the man on the right has a purely decorative slash.

The man on the left has a collar in the carcaille style (tall and standing), while the man on the right has turned the front edges back to create large revers that resemble lapels. He wears his houppelande open down center front, similar to a large overcoat. Both men belt their houppelandes at their natural waist. It becomes popular for the aristocracy to add padding to the shoulder and sleeve cap. These shoulder pads are called mahoitres.

Both men would have on at least one doublet over a chemise beneath their houppelandes. They would also have braies/drawers, full length hose, and a codpiece (a triangular pouch for the genitals attached to the front of full length hose). They would be wearing either pedules or shoes.

The man on the left wears a new chaperon with a roundlet (doughnut shaped pillow) inside. He also has a pouch suspended from his belt. This may be an alms purse.

Here we see a variety of doublets and cote-hardies. The term “doublet” begins to signify a short, fitted garment, usually worn in multiples (possibly one for warmth and 1-2 others of a more decoartive nature). The two men at the left and the second man from the right wear doublets The second man from the right is also wearing an open houppelande over his doublet.

Here we see a variety of doublets and cote-hardies. The term “doublet” begins to signify a short, fitted garment, usually worn in multiples (possibly one for warmth and 1-2 others of a more decoartive nature). The two men at the left and the second man from the right wear doublets The second man from the right is also wearing an open houppelande over his doublet.

A cote-hardie may be worn over these doublets. The two previously unmentioned men are presented in this manner. Cote-hardies are generally longer (usually featuring some sort of drop-waisted attached skirt or peplum). They generally feature controled fullness through the torso, and some sort of large decorative sleeve.

With the short doublet, hose is exposed for the entire length of the leg. If you look closely, you can see a codpiece on the man in the yellow hose. Hose comes in three varieties in this century. 1. footed, 2. with an attached leather sole (pedules), and 3. a footless variety with a stirrup style strap that passes under the foot.

“The betrothal of the Arnolfini” by Jan van Eyck. Oil on Wood. Photo from E.H. Gombrich, “The Story of Art”

The man in this painting wears a new outer garment for this century. It is called a huke and is constructed in similar manner as a tabard. It is seamed across the shoulders, hanging open on sides. However, there is generally more length and fullness in a huke than in a tabard. It was very often lined with fur, and therefore, worn for warmth and display of status. Sumptuary laws regulated the types of fur available for the clothing of the various classes.

The woman in this picture is an example of a rather bizarre fad of the 15th century. Low birth rates combined with the “Black Death” plague of the previous century brought a period of depopulation to this area. It became fashionable in the 15th century for women to appear pregnant. There is even evidence of women wearing abdominal pads and walking with their hips thrust foward in order to enhance this illusion. Houppelandes belted just below the bustline also added to the affect.

She wears a houppelande over a blue gown/kirtle/cote (chemise, hose, shoes underneath) and a variation of a horned reticulated headdress. The “horns” were created from small metal mesh cages named cauls. A caul could be created in any number of different shapes and are an important component in reticulared headdress of all shapes and sizes. The cauls fit over braided and coiled hair and pinned in place. A veil was then draped over top to conceal the rest of the hair.

Follower of Anne, Dauphine d’Auvergne (1358-1410) the wife of Louis II Duc de Bourbon. Sanoian Special Collections Library, Henry Madden Library, California State University, Fresno.

This woman (right) from the early 15th century displays many of the characteristics of the 14th century (for example, tippets, heraldry and the ram’s horn hairstyle). This is more of a transitionary garment than one that is easily labeled as early or late Gothic.

The indicators here are subtle. The squared off neckline, the apparent complexity of construction (resulting in a very smooth, tailored look), and the rather long pointed (piked) shoes all set this outfit a bit more in the 15th century, rather than the 14th.

However, as you can see, many of the 14th century characteristics thrive well into the 15th century.

“Portrait of a Female Donor” by Petrus Christus c. 1455, oil on panel

This woman (left) is wearing a houppelande with its center front edges turned back into revers. It is belted under the bust. The created low “V” neck reaches to the belting. In the base of the “V” we see either a gown/kirtleunderneath OR a modesty panel that buttons or laces into place. Either way, though necklines are lower than they have been before, modesty is maintained with minimum cleavage revealed.

She is also wearing a truncated hennin on her head. As with much of the headdress contraptions of this period, all hair is concealed. It is possible that she has shaved off or plucked out any hair that would have been left exposed. Even eyebrows were plucked to a very thin, faint line or eliminated altogether. A tall forehead was a treasured attribute. A fashionable woman would stop at nothing to acheive it!

Sanoian Special Collections Library, Henry Madden Library, California State University, Fresno.

This noble woman wears a rather large hennin with her houppelande. It was possible for these cone shaped headdresses to reach heights up to 36″ (nobility only, of course). A veil was commonly laid over the hennin as seen here. It was also common for the veil to flow from just the very tip of the hennin.

Another indicator of her status is the fur that lines her houppelande. This is ermine-a luxurious white fur that had flexs of black in it (the black tip was found only on the tail of the ermine). Sumptuary laws regulated this fur to only be worn by the noble class.

Her houppelande is trained. It was possible for this train to be lifted and secured in a number of creative manners in order to protect the fur and to show off a precious privlege (the wearing of ermine).

“A Goldsmith in His Shop, Possibly Saint Eligius”, 1449, by Petrus Christus

This woman wears a variation of the horned style reticulated headdress. This painting was created late in the 15th century. Notice the center front of her houppelande and his doublet. The white in the painting is their chemises. This is an Italian trend that has made its way northward and will be a key identifies for the Italian Renaissance.

His necklace is most likely symbolic of his status and allegiances. These heavy gold necklaces are often referred to as orders.

Marie of Anjou, Queen of France, Late 18th cent.. Artist: Gatine, Georges Jacques (1773-1831). Sanoian Special Collections Library, Henry Madden Library, California State University, Fresno.

The woman to the right wears a truncated hennin and a houppelande with a wide “V” neckline revealing a gown/kirtle or modesty piece.

The houppelande is heavily trimmed in ermine.

Notice her extremely pointed shoe (poulaine) sticking out from under the hem of her gown.

Detail Mary of Clopas, Saint John the Evangelist and Mary Salome from the Rogier van der Weyden painting “Descent from the Cross” –

The lady on the right wears a variation of the new chaperon over a white linen coif. We can see the front lacing of her gown/kirtlethrough the center front opening of her houppelande.

She is of a lower status than the previous ladies. The quality of the material in her attire and the lack of decoration as well as the context of the rest of the painting support this conclusion. The houppelande was a garment common to all classes.

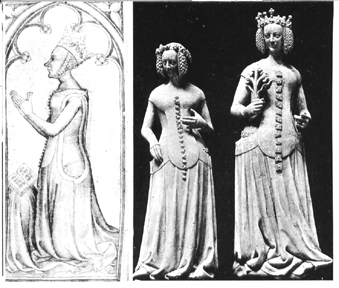

Statues: Isabella von Frankreich with her mother Isabeau de Bavière, der Königin von Frankreic.h

The sideless gown (AKA surcote) is very popular in this century. Very commonly the holes are so large that only a narrow strip attaches the skirt to the collar/shoulder area of the dress. Often this strip is stiffened in order to support the weight of the rather full skirt. When this happens it is given the name plastron.

This style is especially popular with French royalty beginning during the late Romanesque period. It is still seen in the 15th century. The buttons seen here are really jeweled brooches pinned to the front of the plastron. They are purely decorative and do not function as buttons would.

Valiant Ladies”Frescos in the castle, Mantua Piedmont. Photo from A HISTORY OF COSTUME IN THE WEST by Francois Boucher. late 14thc.

These ladies wear heart-shaped reticulated headdresses. These were created using two large cauls on either side of the head. A bourrelet (A sausage-shaped cushion with wire inside that could be bent into a shape) was placed on top of the cauls. The internal structure of the bourrelet held it in the shape that you see here.

QUICK REVIEW

TYPE OF DRESS: tailored with very little draping.

TEXTILES: wool and linen, increased presence of silk.

SILHOUETTE SHAPE: exaggerated triangle. Garments are very long (especially for women) often puddling on the floor. Hanging sleeves add to the width of the lower torso, tall headdress extends the silhouette upward. Males maintain triangle as well, but halfway through the period the triangle inverts so that shoulders are wider and legs are narrow.

BASIC GARMENTS: Layers of tunics (cote & surcote), braies/hose, doublet/pourpoint, houppelande, abdominal pads, huge headdresses (like the hennin), pointed shoes.

MOTIVATIONS FOR DRESS: Status (class differentiation is very important to the noble class) and decoration.

KEY IDENTIFIERS: ‘Windows of Hell” (sideless tunic), fads (dragging, parti-coloring, heraldry, buttons), long pointed shoes (poulaines), pregnant silhouette for women (reaction to population decline due to the plague), hennins and huge reticulated headdresses (heart shaped, horned, use of cauls of all shapes and sizes), invention of the doublet, first codpieces.

Recent Comments