The Restoration (17th Century)

Contemporary Events

- 1685 Louis XIV revokes the Edict of Nantes (which had established religious tolerance in 1598) and resumes persecution of French Protestants. The Huguenots (many of these persecuted Protestants) flee from France and head toward other more tolerant European areas and America.

- Charles II dies suddenly in 1685 leaving no legitimate children. James II (his brother) succeeds to the English throne. He was a devout Roman Catholic and pursued policies that frightened many political factions. Rebellion arises anew. Leaders of English politics invite William of Orange to bring an army from Holland to aid in ending James II’s reign. James flees to France in 1688. William and wife Mary (the protestant daughter of James II) are offered the throne by Parliament.

Late Baroque (Restoration) – 1660-1710

Jan van Noordt, Portrait of a Boy, 1665. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

Restoration doublets take on a “shrunken” appearance. Sleeves, length, and even the ability to button diminish. As a result, much more of the shirt becomes exposed, and the doublet is left looking more like a bolero.

As in the Cavalier period, the shirt continues to take on a more prominent role as a visible part of the ensemble. As the ruff disappears altogether, shirt collars (growing in size) are pulled out and displayed on top of the doublet. Edges often become decorated with lace. In this image the bulk of the collar begins to move forward, under the chin. It has a bib like quality. As the period progresses, collars will again grow narrow and are eventually replaced by early versions of the cravat (a linen or silk scarf, generally in white, that ties around the neck. The cravat eventually evolves into the modern man’s tie).

The young man above is also wearing a new fad–rhinegraves (AKA petticoat breeches). These are closer to modern day culottes than a skirt or bases of the Tudor period. They are a wide legged bifurcated garment. A favorite of King Louis XIV of France, these breeches are often seen bedecked in ribbons and bows. King Louis was fond of accessive decoration, and is often accused of attaching ribbons to any surface that would support them.

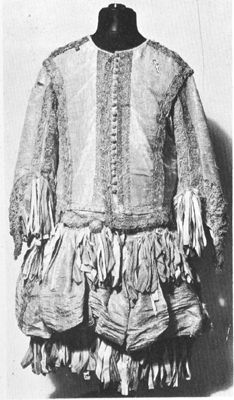

Extant restoration era breeches and doublet.

This doublet and petticoat breeches feature some intense ribbon decoration. This sort of excess would very much please King Louis XIV. The ribbons on this particular suit are made of silk and silver.

The onset of the Restoration period sees a virtual explosion of decor. Many costume historians believe that this was a reaction to political control in England being restored to the monarchy upon the death of Cromwell.

Man in Black, by Gerard ter Borch, c. 1673

The gentleman in the Borch portrait below is a fine example of fashionable dress highly influenced by plain dress. In the early days of the Restoration, alliances to the throne or Parliment were strongly communicated through clothing. This man’s ensemble puts forth mixed messages as to who he was.

For example, the lack of excessive decoration, the sombre color, and the capotain suggest that this gentleman was a follower of Cromwell. His longer hair, the fine construction and silhouette of his garments (namely the “shrunken” doublet and rhinegraves), his shoe and knee bows, and the crispness of his appearance suggest that he has ample wealth and an interest in fashion.

I make the assumption that he is a member of one of the wealthier classes based on these clues. He is chosing to dress this way, communicating his religious/politcal views to his society, but also following the fashionable trends. He is likely a believer in the tenants of the Puritan culture.

The painting is entitled Man in Black. Gerard Ter Borch (the artist) left few clues to the man’s identity other than a detailed study of his clothing.

The Marquis of Tweeddale, 1665

The wearing of wigs comes into practice during the 17th century. It is suspected that this is a reflection of the fact that Louis XIV went bald and he, out of vanity, took up the practice in maintenance of his appearance.

Nonetheless, men begin cropping their hair short (or shaving it off altogether) and adopting large flowing tresses. By the end of the period, some of these wigs are powdered. However, natural colors are almost universally favored for most of the Restoration.

Notice the excessive ribbon decoration in this portrait. The ruffles of lace at his throat is evidence of the cravat‘s evolution.

Extant Restoration era petticoat breeches and doublet.

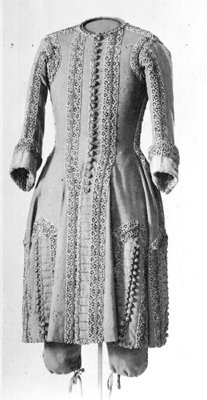

Extant early 3 piece suit: justacorps, waistcoat and breeches

In 1666, Charles II–newly restored King of England–was not a supporter of the excessive amounts of embellishment and volume that characterizes early Restoration dress even though it was a celebration of his return to the throne. Through consultation with his personal tailors, he instead adopts a new style of dress that costume historians claim is the origin of the modern day 3 piece suit.

It featured a long, collarless, sleeved coat (called a justacorps or surtout). Under this was worn a waistcoat which was cut in a similar line as the justacorps. It, too, was sleeved. (The shirt was worn underneath the waistcoat). The waistcoat hem was a few inches shorter than the coat. The breeches that accompanied this ensemble were narrow, but not tight. They tapered toward the knee. When the justacorps was buttoned from neck to hem (which it had the ability to do), the waistcoat was completely hidden. Breeches peeked out just below the hem. Buttons spaced so closely that they were nearly touching one another was a very common decorative feature.

Charles II vowed that he would wear this style of dress until he passed from this earth. He, of course, did not stay completely true to this vow. However, his influence over men’s wear is felt through the remainder of costume history. From this point forward, France is no longer the European fashion leader for men’s wear. England is in the spot light.

Matthew Prior. Simon Belle, ca. 1705.

The justacorps, waistcoat, and breeches ensemble becomes the dominant male silhouette. Lace trim, embroidery, and other forms of excessive decoration can still be found amongst the wealthy. However, the overall silhouette is much more contained and masculine when compared with that of the early Restoration. If fashions explode with excessiveness and fluff in the wake of the Restoration (an expression of personal freedoms) then that excitement sobers up as we move into the latter part of the period. Europe is getting growing more serious and “back to business.”

Through the remainder of the 17th and into the 18th centuries, France will follow the lines of the male silhouette, but will always go much further with decoration–lace, embroidery, ribbons, etc. The French male silhouette will always appear a bit more feminine than that of the English.

Wigs are becoming the dominant head dressing amongst fashionable men. They grow to such heights, that it becomes difficult to wear hats, although etiquette strongly encourages one to do so. It becomes common practice to carry one’s hat beneath one arm as a polite option. Hats intended for this purpose are callled chapeau bras. They were hats with a slightly flatttened crown as they were not meant to be worn, but carried under one arm. The gentleman on the left below carries one.

Both of these men are wearing their justacorps open down center front, revealing their waistcoat. Notice the large cuffs–much wider than the sleeve themselves. This becomes a common feature of the justacorps. Sleeve lengths terminate well before the wrist, leaving ruffles on the shirt exposed. Notice pocket placement as well. They are often placed only a few inches from the hem of the coat. These are also key Restoration traits.

Both of these men are wearing their justacorps open down center front, revealing their waistcoat. Notice the large cuffs–much wider than the sleeve themselves. This becomes a common feature of the justacorps. Sleeve lengths terminate well before the wrist, leaving ruffles on the shirt exposed. Notice pocket placement as well. They are often placed only a few inches from the hem of the coat. These are also key Restoration traits.

The gentleman at the right has a rather large muff suspended from his waist. The muff was a common accessory for both men and women during this area. They are generally made of fur, and provide a place for the hands to slip inside for warmth.

Both men wear high heeled shoes with square-ish toes and a tall vamp (or tongue).

Fra’ Galgario (Vittore Ghislandi), Ritratto del conte Gerolamo Secco Suardo. 1711

The gentleman in the long white wig wears an old fashioned style when compared to contempory images, especially when presented with the fact that this portrait was painted in 1711 (the end of the period we consider to beRestoration). It is, once again, evidence of the fact that people hold on to what they like despite fashion trends. The extremely powdered wig and cravat are practically the only early 18th century influences at work here. The rest of his attire is characteristic of styles 50-60 years prior. He is yet another fashion anomaly–of which I seem to be growing fond.

I, personally, find it remarkable that at this point in history fashions that I would consider to be more feminine (rhinegraves, the bolero style doublet, and blousey shirt) are the choices for conservative attire. While the more rigid, regimented line (coat, waistcoat, breeches) is considered cutting edge fashion. It is an interesting game that context plays and a fun fact to play with when staging Restoration comedies for modern audiences.

Barbara Palmer (née Villiers), Duchess of Cleveland

The politics of the Restoration bring with it a new fashionable attribute for women–feminine sensuality. The true position of power for a woman comes not from the status of being the wife of a powerful man, but from being his mistress.

As a result, for a brief time, it becomes fashionable for a lady to be portrayed as if she has just taken a tumble in the broom closet. This trend in 17th century fashion of ladies being painted in reclining positions and appearing somewhat unkempt and disheveled is referred to as dishabille/deshabille (translated as “undress”).

SIR PETER LELY (1618-1680), Portrait of a Lady (England, c.1670). London. England

These 17th century mistresses presents themselves in a very careful, deliberate state of undress. Everything about their appearance is soft, sensual, and powerful. These are the qualities that characterize the most fashionable women of this era.

Pay particular attention to the fullness and line of her chemise. Notice that not only is the neckline of her bodice rather low and plunging, but it is just barely perched upon the shoulder. Much more skin is exposed above the bust line.

Notice her red lips and fingernails. These are not naturally this hue, but painted with cosmetics. Her cheeks are rouged. She may also be wearing foundation in order to enhance her much desired paleness.

Sir Patrick Lely, Portrait of an unknown woman. Tate Museum. London. England

I include these images here, solely because I find their history interesting.

Some dishabille images, such as the Lely portrait on the left, go to new extremes. The bare breast (an artistic convention, I assure you) does not imply that she is a lady of ill repute. Instead, it indicates that she is the mistress of a very powerful man. The presence of the spaniel on her left (the observers right side) reinforces this notion. This particular breed is symbolic of the Stuart royal family.

Sir Patrick Lely, Elizabeth Killigrew, Mistress of Charles ii

The title of this portrait is Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare circa 1679

The woman in the Lely portrait at the right is Elizabeth Jones Killigrew, eldest daughter of the 1st Earl of Raneleagh. She was considered one of the greatest beauties of the Restoration court. She was King Charles II’s mistress in the 1670s at the time this painting was created (c. 1679). Interestingly, the portrait bears the title Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare. She did not marry the Earl of Kildare until 1684. The title of the painting may have been changed in order to divert attention from her life prior to her marriage.

Barbara (Villiers) Duchess of Cleveland (1641 – 1709) mistress of Charles II, wife of Roger Palmer, Earl of Castlemaine. 1666. Getty Images.

Logic tells us that it would be rather difficult to walk around with our clothes falling off our bodies, such as the previous paintings suggest. However, the softness and sensuality of the dishabille look did influence the slightly more conservative, yet undoubtably fashionable wives of the day.

Notice the low and wide neckline perched upon the shoulders and the soft, rumpled looking silk satin used in her gown. Again, we see red lips and rouged cheeks.

Just like masculine fashions, the silhouette tightens up again during the second half of this period. Much of the softness (particularly in the torso) disappears from women’s wear during the later decades. The silhouette is much more architechtural.

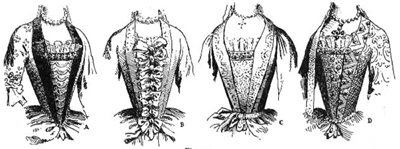

Maurice Leloir. Histoire du Costume, Volume 10, 1678-1725

Two new fashion innovations that propel this new stiffness are the fontange/commode headdress and the new mantua/manteau gown.

The fontange began as a bow used to draw bangs up out of the eyes (growing out now from the trend of cutting them short during the Cavalier eras). The bow quickly grew into a series of lace ruffles supported on top of the head with a metal frame. It generally featured a length of lace in the back that hung down and covered the hair.

The manteau gown was initially rather unfitted, and was cut in one peice from shoulder to hem. It was inspired by an Eastern fashion. It quickly evolved into a dress that featured shaping through darts and vertical seams. A horizontal seam connecting bodice and skirt does not exist. The gown takes on a jacket-like appearance. It is generally worn with the skirts pulled toward the back (revealing the modeste) and often piled upon the rump. This creates a silhouette that ominously foreshadows the 19th century Bustle period.

Maurice Leloir, Histoire du Costume, Volume 10, 1678-1725

Due to their jacket-like construction, the manteau gown often left the busk of the stays exposed. A decorative stomacher was attached to the front of the gown or stays in order to hide the undergarment. These stomachers were interchangable, and one could easily change the appearance of the gown simply by changing the stomacher.

As we see here, the fashionable waistline placement for the Resoration period returns to a more natural placement.

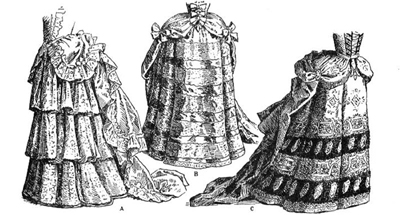

Maurice Leloir, Histoire du Costume, Volume 10, 1678-1725

Three examples of manteau gown skirts and the modest petticoats that are revealed due to the pulling back of the skirts.

I cannot help, but think, “Bustle, bustle, bustle,” when I see these images.

“Colonial Clothing: Dutch lady, 1660”

Full cut coat-like garments such as the one shown here in red are pictured in a number of portraits from the period. They are most often portrayed in scenes within the home. It is assumed that they were garments worn at home to provide relief from the tightly laced “street” garments and/or pregnancy attire. Their fullness hides a bulging belly quite nicely.

He is wearing:

drawers

shirt-collar has shrunken back to a natural size.

cravat-Tied around the neck over the collar–loose ends hanging below the chin.

stockings and heeled shoes

waistcoat-cut in a similar manner to the justacorps, hem hangs a few inches shorter. It is most likely sleeved.

justacorps– 3/4 length sleeves with a large cuff, has the ability to button from neckline to hem.

breeches- moderate fullness, ending just below the knee.

long wig

feathered hat

She is wearing:

chemise

stockings and heeled shoes

at least one secret

stays-cut to match the fashionable silhouette–low neckline, and natural waistline.

modeste

manteau gown-with skirts pulled to the back and waistline returning to a “natural” location.

some sort of hat

These three ladies demonstrate the three principle female silhouettes seen across Europe during the Restoration period.

These three ladies demonstrate the three principle female silhouettes seen across Europe during the Restoration period.

I’ve been referring to these silhouettes as:

(from left to right)

Fashionable, Spanish, and Plain Dress.

The countries listed under each lady in this image indicate the regions where these silhouettes are most prevalent.

Portrait of a couple, 1661, Bartholomeus van der Helst

QUICK REVIEW

TYPE OF DRESS: Tailored. Doublet will phase out to be replaced with more complicated 3-piece suit.

TEXTILES: Same as Cavalier period

SILHOUETTE SHAPE: Initially, explosion of decoration. Initially, men are again rather triangular, women are an hourglass with exaggerated influence on the head. 1666 a new male silhouette is adopted. This mirrors the ladies: an hourglass with exaggerated influence on the head.

BASIC GARMENTS: Men: shirt, collar, doublet (fading), petticoat breeches/rhinegraves. NEW: narrow leg breeches, shirt, waistcoat, surtout/justacorps, cravat, hats, wigs, stockings, shoes. Women: same components as Cavaliers. NEW: fontage/commode.

MOTIVATIONS FOR DRESS: Status as it relates to politics and religion.

KEY IDENTIFIERS: bolero style doublet, excess amounts of fabric in shirt and breeches, ridiculous level of embellishment, full bottomed wigs, first 3 piece suit, early suit coat is collarless and buttons from neck to hem, eventually the early suit coat adds pockets a few inches above the hem and large cuffs with sleeves ending short of the wrist, ladies mantua dresses pulled into “bustles”, footage/commode. Increase of “plain dressers” in rebellion to the excesses of royalist styles.

Recent Comments