The Roaring 20s

Contemporary Events

- The early 1920s brought unparalleled prosperity for America. Business boomed, particularly commodities such as automobiles, radios (broadcast began in 1922), rayon, cigarettes, refrigerators, telephones, cosmetics, etc. Despite the boom in production, the american farmer was already struggling: especially in the realm of exports and decline in cotton (rayon was more popular).

- Silent films had become a very popular and common source of entertainment by the onset of this decade. The first “Talky” film was released in 1927.

- The 18th Amendment took effect in 1920, making the distilling, brewing, and sale of alcoholic beverages illegal. Saloons were replaced by secret “underground” Speakeasies. Black Market trade and bootlegging of alcohol gave rise to the Mafia.

- Chain stores and purchasing large ticket items on installment plans (credit) becomes common during this decade.

- 1927: Charles A. Lindbergh completes the first transatlantic flight. Commercial passenger service begins at the end of the decade.

- The prosperity bubble waivers beginning in 1927, however the stock market continued upward trajectory. October 29, 1929 (after a number of market drop/recovery periods) the Stock Market plummeted without recovery. The United States and Europe enter the era referred to as “The Great Depression”.

The Ladies of the Roaring ’20s

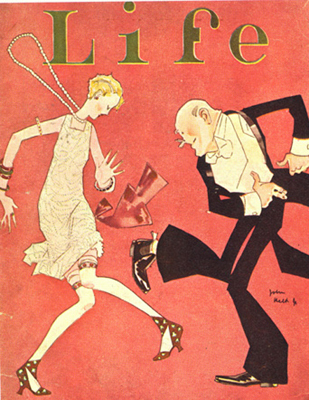

In cover illustrations artist John Held Jr. affectionately satirizes the flapper’s dances, etc., American, 1920s. This cover was from the February 18, 1926 edition of LIFE Magazine

This Fabulous Century: Volume 3 Ð 1920-1930. New York: Time-Life Books, 1970. p. 52.

Inspired by teens and college students “The College Man” and “The Flapper” are the fashion icons of the 1920s. John Held, Jr. captured the spirit of these icons for the covers of popular 1920s magazines.

The speakeasy, the “Charleston”, the automobile, the public use of profilactics, and changing standards of female behavior (ie. drinking, smoking, spending time with boys without a chaperone) manifested themselves in a brand new look for women–a youthful masculine one. Never before in the history of Western costume did women wear skirts revealing their legs, extremely short hair, and purposefully obvious makeup. Women also begin the practice of dieting in hopes of achieving the new fashionable figure–a slimmer, flatter boyish shape.

The College Man pictured here is wearing Oxford Bags. These trousers were a fad started at Oxford College in England. With cuff widths as wide as 32 inches in diameter, these baggy trousers provided a solution to students prohibited from wearing their knickers to class. The style allowed them to change quickly from regulation length pants to knickers (underdressed, of course) in order to play sports between classes. These trousers were also seen in the US among the trendy youth. The average man never wore them, but the cut of the fashionable trouser was wider and fuller through the leg as a result of their influence.

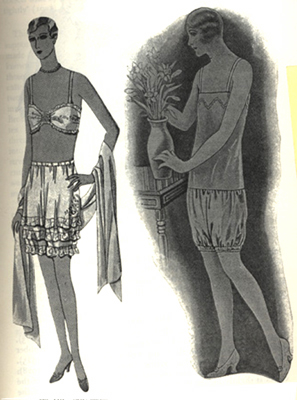

BRASSIERE AND DRAWERS, 1927; (right) CAMI-KNICKERS, 1926

Cunnington, C. Willett. The History of Underclothes. NY: Dover, 1951. FIG. 110.

While the requisite amount of underwear worn by a lady again decreases in this period, “foundation” garments take on a new role during this decade. Underwear’s primary role is to suppress the curves of the woman who did not have the fashionable flat, boxy figure.

Brassieres become quite similar to modern bras, however rather than being bust enhancing they were bust flattening. Knickers/bloomers assume the name panties, and were constructed along the lines of what we call “tap pants” today–wide legged, shorter than pervious periods, with a possible elasticized waist.

The woman on the right is wearing cami-knickers(also known as a teddy or step-in). This garment combines the camisole and knickers into one piece. Notice that the fashionable waistline is maintained in the undergarments. It was quite possible–if the woman was blessed with the desired figure–for a lady to wear only this as her underlayer.

Corsets, slips and garterbelts were also available if she desired them.

Left: DRESS AND SASH C.1923-25. Made in the United States. Silk chiffon with bead embroidery. Right: DRESS AND SASH c.1928-30. Made in the United States. Printed silk chiffon with a velvet ribbon sash.

Blum. Dilys E.. Best Dressed: Fashion from the Birth of Couture to Today. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997. p.33.

Fashionable dresses of the 1920s were cut with a straight torso without an indention at the waist. Instead, the fashionable waistline was dropped to rest upon the hip bones (also known as the high hip). Most dresses were of the one piece persuasion.

Neckline styles featured most of the usual shapes–jewel, “V”, cowl–but they were cut slightly deeper. Soft, drapey fabrics were usually favored (such as the silk georgette pictured here) with bias cutting finding exploration towards the end of the decade.

Hemlines gradually shorten–hovering around kneelegth by mid to late decade. Uneven hems created through layered panels (handkerchief hem) or through the insertion of triagular or square godets were favored during the late 1920s. Scalloped hemlines were also fashionable.

JEANNE LANVIN. Robe de style, summer 1924. Black silk taffeta with green silk and sequin embroidered medallions and silver corded net. Note the Chinese influence on the decorative motifs.

Martin, Richard and Harold Koda. Haute Couture. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995. p. 78.

Jeanne Lanvin introduces a bouffant skirt as an alternative to the boyish flapper silhouette. She called the look robe du style. The dress retained the dropped waistline, but had a very full skirt creating a silhouette slightly reminiscent of the Crinoline Period. The robe du style favored stiffer fabrics that added volume to the skirt–such as silk taffeta pictured here.

Regardless of cut, evening dresses of the 1920s were often decorated with extensive beading that sometimes covered the entire dress. Beading patterns included Art Deco and Eastern motifs. Fashionable fabrics for evening dresses included chiffon, soft satins, and velvets. These fabrics, once heavily beaded, would literally drip off of the body.

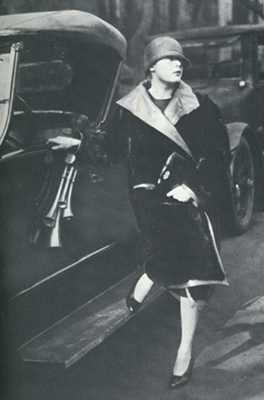

Poised and chic, the epitome of the sophisticated flapper, Suzette Dewey, daughter of the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, steps out of her roadster. American, 1920s.

This Fabulous Century: Volume 3 Ð 1920-1930. New York: Time-Life Books, 1970. p. 31.

By the 1920s the automobile had become valued as practical transportation rather than solely for sport or entertainment. As a result, special costume for “motoring” disappeared. Instead, the automobile eliminated some trends in everyday attire while reinforcing others. These included:

–shorter less cumbersome skirts (long skirts got in the way of driving as well as getting in and out of the vehicles).

–Parasols were no longer used. They were not practical in open or close topped automobiles. Women also walked less.

–Walking sticks and canes also go out of style. Men, too, walked less.

–Wristwatches (first used during WWI by Army officers) are easier to read while driving.

–Hats are smaller. The cloche (as pictured here) becomes the definitive style. Wide brims easily blew off in open top autos and were awkward in those with closed tops.

The coat that this woman wears is very typical of the period–boxy and closing over the left hip most likely with a single large decorative button or several small ones.

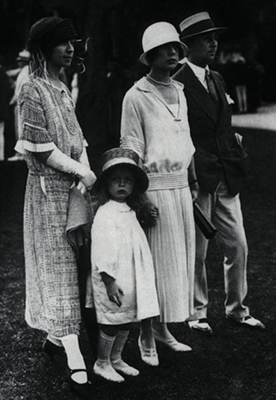

These afternoon dresses, one of which was made along middy blouse lines, were worn to watch the tennis matches at the Newport Casino.

Milbank, Caroline Reynolds. New York Fashion: The Evolution of American Style. NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1989. p. 77.

Even conservative women subscribed to the fashionable boxy silhouette of the 1920s. They may have never attempted the extremes that characterized the iconic flapper, but the trademarks of the silhouette become quite universal. The dropped waist, the cloche hat, and the tubular silhouette were adopted by most women of all classes.

Due to shortened hemlines, shoes take on a greater importance to the overall ensemble. As a result, more attention is devoted to decorating this important new accessory. A 2 1/2 inch heel (either the still popular Louis heel or the new Cubanshape) was quite common; as were multiple straps across the instep. Toes could be pointed or rounded.

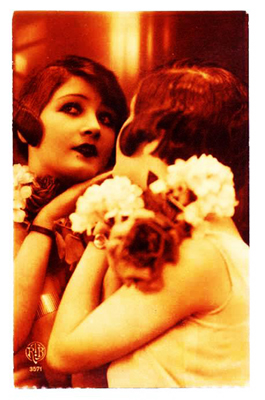

Postcard of a flapper, 1920s

Cosmetics were an accepted part of women’s fashion in the 1920s. Before this time a woman who used them, either did so in secret or was of a questionable reputation. During this period makeup is essential to the desired look.

Fashionable ladies plucked their eyebrow into a narrow line which was then emphasized with eyebrow pencil. Bright shades of rouge and lipstick were preferred. Lips like Clara Bow‘s were every girl’s desire. She would pencil in a puckering cupid’s bow shape. Eyes were rimmed with liner and smokey eyeshadow. The whole look was completed with heavy powder, creating an almost masklike appearance.

Women’s hairstyles of the 1920s were one of the most revolutionary developments in fashion. Expect for the Empire period, no other period can be cited in which women cut their hair so short. By 1923, it was an accepted fashion to have bobbed hair. The most extreme bob look was the shingle bob. Hair was cut short in the back like a man’s and left a little longer in the front. The Eton crop was the shortest style of all (pictured below in the left image). For all intents and purposes it was a man’s haircut worn by a woman.

Boys and girls in California brazenly puff on cigarettes. American, 1920s.

This Fabulous Century: Volume 3 Ð 1920-1930. New York: Time-Life Books, 1970. p. 29.

This beaded, fringed evening dress was modeled by a Hollywood starlet and is thus more fitted than the usual chemise frock; film actresses were loath to hide their figures, no matter what the going style, whereas on Broadway, a chic and up-to-the-moment look was more important.

Milbank, Caroline Reynolds. New York Fashion: The Evolution of American Style. NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1989. p. 81.

Recent Comments