Neoclassical (English Regency/French Directoire)

Contemporary Events

- Once George III was declared unfit to rule England (1810), his son (the Prince of Wales) was named Regent to act in the place of his father. This period, 1811-1820 is thus referred to as “The Regency Period” in England. The Prince Regent was considered extremely fashionable and had a passion for the pursuit of ladies. He was nicknamed the “First Gentleman of Europe” and from this moment forward, London becomes the center for male fashion. Upon the death of his father, the prince becomes George IV.

- In France, the new republic is short lived. Napoleon Bonaparte (a member of the Directoire ruling France) becomes head of state, the Napoleonic Empire is established. After his overthrow, the monarchy is restored under Louis XVIII in 1814. Throughout the remainder of the century, France will experience a variety of governments. Regardless of the turmoil of the government, one thing remains strong: Paris is the unchallenged center for female fashion.

- In the newly minted United States of America, 16 states (all east of the Mississippi River) comprised the union. Westward Expansion is on the horizon.

- The Industrial Revolution which truly began in the preceding century, is on the verge of acceleration.

Neoclassical Women (1800-1820s)

May 5, 1790, Plate 2. Issue no. 8. Journal de la Mode et du Gout, Fashionable dress.

While the French Revolution (1789) cuts the history of costume like a knife, the initial effect on women’s clothing is merely a deflating of silhouette. The line and construction of this 1790 walking dress closely resembles that of other late 18th Century dress. It especially reflects the fad for “country” attire that swept women’s fashion during the late Rococo/Georgian period (click here to view styles of dresses from the previous period. Click the “back” button on your browser to return).

Nonetheless, never before has fashion changed as radically or as quickly as it did between the years of 1789 and 1800.

This is mostly due to the new French Empire led by Napoleon Bonaparte. Due to Napoleon’s multitude of military campaigns into Italy many statues and artifacts from Greco-Roman ruins found their way back to France. Historians believe this to be the main fuel for a revival of all things “classical” (meaning Greek & Roman) at the tail-end of the 18th Century. These classical ideas affected everying–literature, governments, and most importantly to us…fashion.

Women in Morning Dress, Kensington 1794

The saying goes, “It’s all been done before.” This is as true of fashion as anything else. For the first time in costume history, the prevailing fashion clearly imitated fashions of the past–a trend that reoccurs frequently through the rest of the history of dress. Women’s fashion of the Empire/Directoire period clearly “reinterprets” Greek and Roman dress. However, it is done without a true understanding of how the garments actually functioned.

Vase paintings and statuary were studied intently and garments were created in imitation of their findings. However, the resulting dresses were much more complicated in construction than the rectangles and squares of fabric draped around the bodies of the past. (Click here to see examples of Greek dress. Click here to see examples of Roman dress. Click the “back” button on your browser to return).

The fashion plate pictured above features morning dresses from 1794–merely four years after the previous plate. The shift towards the “classical” line is obviously in place. There is still quite a bit of poofiness and fussiness (especially in their accessories). View this image as a transition between the styles characteristic of the 18th century and those of the simpler, “Neo-Classical” line.

Dress with train, white embroidered linen, c. 1800 (Kohler)

Initially, lightweight–sometimes relatively sheer–white fabrics prevailed for the new fashion. The once colorful Greco-Roman statues had been bleached white from exposure to the elements. The imitators of the late 18th/early 19th century interpreted this fact to mean that all of the clothing was also white, thus the choice of white for the neo-classical dresses. Eventually, pastel dresses became fashionable as well.

Underpinnings went through a revolution of their own. For the first time since the onset of the Elizabethean Era, the desired female silhouette allowed the body to be of a fairly natural “columnal” shape. The required understructure was minimal. Most corsets served to support and lift the breasts (the zone of emphasis for this period). As a result, most women favored a short corset that stopped just below the underbust, since this is the point that becomes the fashionable waistline. (Some women still wore a long corset. However, these did not cinch the waist as corsets of the previous and following periods did, but instead slimmed the hips into a space slightly bigger than the waist. Thus, a curvy woman could acheive the desired column-like sihouette). Chemises and petticoats were optional. The most fashion forward women dispensed with them altogether.

As a rule: Empire/Directoire gowns were universally high waisted, emphasis was on the bosom, and the resulting silhouette was tall and vertical. Headdresses were generally either a variation of a bonnet-style or a Greco-Roman inspired headwrap.

Other common accessories included reticules/indispensibles (small pouch-like hand bags that dangle from ladies’ wrists), tall gloves (that covered the forearm), and parasols (used to protect a ladies’ complexion from the sun). Also, dainty matching jewelry sets that included necklaces, earrings, and bracelets were very common. All of these things can be found in the fashion plates at the right.

“Morning Dress and Full Dress”, The Lady’s Monthly Museum, By a Society of Ladies Vol. XVI London Published by Vernor and Hood Jany. 1. 1806

Large rectangular shawls were also very popular during this period. These were very reminiscent of the pallas and himations used in fashionable Greco-Roman attire. These accessories were fashionable as well as functional. They provided much needed warmth that the fashionably thin dresses could not provide.

Also, notice the woman’s hairstyle on the right. It shows strong Greco-Roman influence. Statues and artifacts influenced ALL aspects of fashion.

Fig. 29. Spencer (1801). D’apres un spencer de la societe de l’Histoire du Costume.

This woman is wearing a spencer (a tailored short jacket that ended at the fashionable waist–or underbust–of this period). These “cropped” jackets featured fairly complex construction for their diminuative size. Notice the seam lines in the back of this particular example.

Portrait of Laure Bro, 1818. Painted by Theodore Gericault.

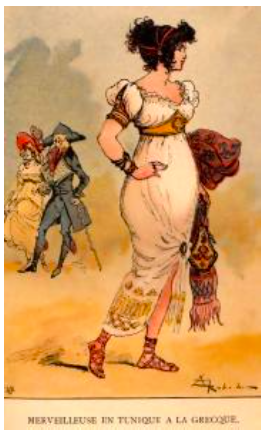

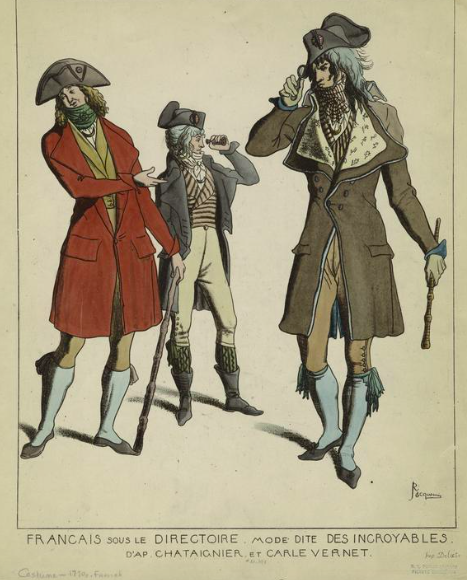

Incroyable et Merveilleuse in Paris

The subjects of this plate could be considered an incroyable (the man) and a merveilleuse (the woman). Literally translated as the “incredible ones” and the “marvelous ones,” incroyables and merveilleuses took Empire/Directoire fashion to the extreme.

The extremely tall cravat, nipped in waist, very wide lapels, unkempt hair, and what seems to be extremely tight pantaloons are the signs of an incroyable. The extreme sheerness of her gown and the lack of substantial undergarments resulting in an embracing of the natural female form are signs of a merveilleuse. Merveilleuses were also reported to favor pale pink tights (as if their legs were blushing from being exposed), very low necklines (emphasizing their breasts), skirts with exceptionally long flowing trains, oversized hats, and wild unkempt hair.

Notice her Greco-Roman inspired footwear.

Original Engraving by By Carle Vernet ( French, 1758 – 1836)

Neoclassical Men (1800-1820s)

George “Beau” Brummell, watercolor by Richard Dighton (1805) Caricature of Beau Brummell done as a print by Robert Dighton, 1805.

For the remainder of Costume History, men’s fashion changes much more slowly than women’s clothing. Prior to this period male and female dress were equally grand and equally flamboyant. Beginning with the French Revolution, male attire becomes more and more sedate–devoid of qualities now considered acceptable only in feminine attire (ie. bright and bold colors, lace, embroidery, excess of decoration, etc.). Lavish fabrics lose favor to practical ones. This trend begins in England, where the tailors had been building a strong reputation for generations. Now, London, instead of Paris, becomes the fashion leader for male attire.

None of the components of male fashion changes drastically from the previous century, including silhouette. They still wear a coat, waistcoat, shirt, pants, and cravat just as before. However, it is the way that they are worn that changes.

The biggest changes in men’s attire were propelled by George “Beau” Brummel, a close friend of the English Prince Regent. Brummel (at left) was known for his impeccable dress aesthetics including beautifully tailored English coats. His clothing was always immaculate–linen shirt and cravat were precisely pressed and starched. Brummel had the peculiar belief that it was necessary for a gentleman to bathe at least once a day–and often took the opportunity himself to indulge in more than this. Of course, this gave him opportunity to frequently change his “linens” perpetuating his crisp image. Beau Brummel set the fashions at court until he fell out of favor with the prince. He was an icon for the Regency Dandy (a man who was well dressed, circulated in the ‘best’ of society, who was always ready with a witty comment and whose chief preoccupations was with fashion).

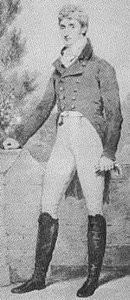

1802. Earl Haddington in morning dress

This image is of the Earl of Haddington. Notice, that like many of his contemporaries, he has pretty much copied the attire of Beau Brummel. The following things were common in the male Regency/Directoire wardrobe:

–Tall boots. Fashionable male attire of the early 19th Century evolved from riding attire of the 18th Century. The knee boots favored by Regency men are a direct example of this.

–Waistcoats were commonly cut straight across and were about 2 inches longer than the coat (The Earl’s is white).

–Tight fitting fall-front pantaloons.

–Common accessories: watch fob (dangling from his waist near his right elbow here) and gloves (clutched in his left hand). Another common accessory is a cane (not pictured here). It is believed that canes gained favor once the carrying of swords was outlawed sometime during the previous century.

—Top hats (also not pictured here) become the most common headdress, replacing the tricornes of the previous century.

Portrait du peintre Pierre Guérin (1774-1833) Auteur : Lefèvre Robert (1755-1830)

In this painting we are able to observe much of the “crispness” of dress that Beau Brummel popularized. The gentleman’s cravat is pristinely white and well pressed. It is wound tightly around his neck from collarbone to chin. We can assume that his shirt is equally pristine.

Instead of a tailcoat, this gentleman is wearing a frock coat (notice the full skirt). Still considered a “casual” coat this would be an appropriate ensemble for morning or sporting dress. In periods to come, this coat will become more accepted for day wear.

In this painting we are able to observe much of the “crispness” of dress that Beau Brummel popularized. The gentleman’s cravat is pristinely white and well pressed. It is wound tightly around his neck from collarbone to chin. We can assume that his shirt is equally pristine.

Instead of a tailcoat, this gentleman is wearing a frock coat (notice the full skirt). Still considered a “casual” coat this would be an appropriate ensemble for morning or sporting dress. In periods to come, this coat will become more accepted for day wear.

The following images are reproductions of period garments.

They are for sale at http://historyinthemaking.org.

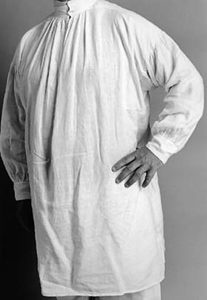

Shirts were made of cotton or linen and were cut full through the chest. Regency shirts took on a pristine neatness and lost all of the frills of the past. They did not open all the way down to the waist as a modern shirt does, but had a placket center front that ended mid-chest (generally closing with 3-4 buttons). While this shirt has a moderately sized band collar, it was very common for shirts to have tall collar points reaching above the chin. These were called ears. Conservative men folded the ears downward, while the dandy allowed them to point upwards with a cravat wound from collarbone to chin.

The bottoms of shirts were square-cut until the middle of the 19th Century when they become curved like modern shirt tails.

While knee breeches are a thing of the past for the fashionable, they linger a bit among older, conservative  gentlemen for formal occasions.

gentlemen for formal occasions.

Regency trousers and pantaloons had what was called a fall front instead of the modern fly front. The waist band buttoned behind a rectangular flap (AKA Fall). Trousers are cut fairly narrow through the leg and reach the ankle. Pantaloons are very tight, almost like a second skin. They are often made of knitted material to better hug the leg and had a strap that passed under the arch of the foot to prevent them from riding upward.

Regency men often wore braces(suspenders) with their trousers or pantaloons. Braces buttoned on to the pants and held them in place. When worn with pantaloons, braces and the strap beneath the foot maintained a taut, smooth appearance.

Waistcoats are much like the modern vest in both construction and function.

Since generally only the front of the waistcoat was seen the back was usually constructed of a much less expensive fabric. The waistline could be square cut across the waist or it may be cut into two points like the modern vest. Single and double breasted variations were common. Collars either stood up or turned back into lapels/revers. Shawl collars were especially popular for waistcoats.

Some fashionable men wore more than one waistcoat in layers. Look to the collar edge to see if more than one waistcoat is present, since this is often the only place that it is apparent.

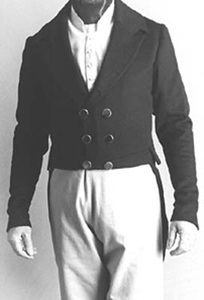

The most common Regency coat was a tail coat. While the front of the coat pictured here  comes to the natural waist, it was more common for the the waist of the coat to end a few inches shy of the waist. This allowed the bottom 2″ of the edge of the waistcoat to show below the waist. (This model is shown without a waistcoat…this is NOT a common look of the period).

comes to the natural waist, it was more common for the the waist of the coat to end a few inches shy of the waist. This allowed the bottom 2″ of the edge of the waistcoat to show below the waist. (This model is shown without a waistcoat…this is NOT a common look of the period).

The Regency tail coat was cut without a seam at the waist, which gave a distinctive cut away curve at the hip and generally created a soft wrinkling of the coat below the arm. (This is seen most clearly in the Brummel and Haddington images above). Sleeves are long–ending at or just below the break of the wrist–and sit high on the shoulder. Shoulders are unpadded creating a natural silhouette.

The most common neckwear item was still the cravat. These were long rectangular strips of cloth (60″x10″ on average) that were wound around the neck over the tall collar of the shirt. Starched muslin or taffeta were commonly used–Black and White being the most common.

An alternative to a cravat was the stock (shown here at the left). These were stiff neckbands that fastened in the back with buckles and/or ties. They were often worn with shirts that had shorter band collars (as pictured above). They created a cleaner and smoother appearance. A white stock often was worn with a black ribbon called a solitaire (tied over the stock).

QUICK REVIEW

TYPE OF DRESS: Tailored with the illusion of draping.

TEXTILES: Fabrics are simpler and less decorative on the whole, particularly at the beginning of the period. Ladies dresses favor cottons and linens. Men’s suits favor wool. Silks will return to ladies’s dresses in the second half of the period.

SILHOUETTE SHAPE: This is the most drastic silhouette change that we have seen so far. The 18th Century was extremely wide, the early 19th becomes tall and narrow. The shape is columnar like the Ancient Greeks.

BASIC GARMENTS: Men: 3-piece suit (tail coat, waistcoat, pantaloons) worn with a shirt and cravat OR stock & solitaire. Women: dresses inspired by ancient greek statues with an elevate waist, flat “ballet” style slippers or sandals, large draped shawls, spencers, bonnets. Undergarments may include a chemise, petticoat, and short stays (more like the modern brassiere than the 18th Century corset).

MOTIVATIONS FOR DRESS: Status: a conscious dissociation with “aristocratic” fashions (elimination of knee breeches, powdered hair/wigs, elaborate/excessive decoration). Hygiene. If you are clean and pristinely dressed = higher status.

KEY IDENTIFIERS: Imitation of Ancient Greek dress for the ladies: thin gowns with the waist elevated to just below the bust (inspired by the chiton) worn with large shawls (inspired by the himation), dark tail coats that are slightly short in the waist (waistcoat sticks out 2″ below) with light colored tight fitting pantaloons and boots, very tall collars on shirts often worn standing up, top hats.

Recent Comments